Do you know your New Zealand sports history? Try this one out.

Name the two-time New Zealand amateur golf champion who rode a winner in the New Zealand Grand National, whose horse remains the only New Zealand-bred and owned winner of the British Grand National, and who set a British rowing record for rowing in a three-man team from Oxford to Putney, while also winning club golf events at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club at St Andrews and coaching his son to an Olympic silver medal in rowing?

That man was Spencer Gollan, an early contender for New Zealand's most complete sportsman given all-round skills that saw him twice a winner of the New Zealand Amateur Golf Championship, a record-holder in long-distance sculling in England, an outstanding marksman, tennis player, swimmer and racehorse breeder.

Multi-talented sports achiever Spencer Gollan

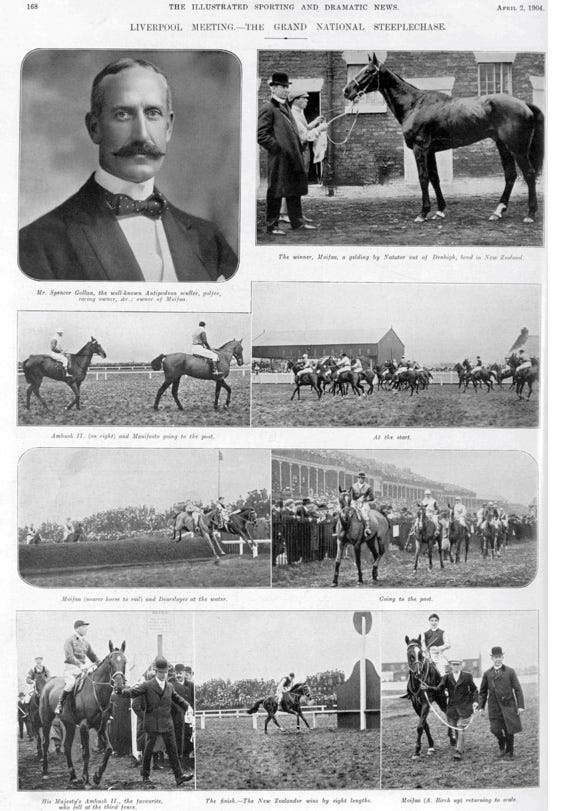

In the latter capacity, he achieved his most noteworthy feat when racing New Zealand's only winner of Aintree's Grand National, Moifaa.

Many stories have been told about the deeds of the 1904 Grand National champion, but one of the most prevalent is also the most erroneous. Various publications have told the story of Moifaa being shipwrecked en route to England to race, only to have swum free of the wreck to be rescued from an island some distance from the sinking.

Sadly, that horse was not Moifaa, although it did run in the same Grand National. The stories may have been confused by the fact that an Australian entry in the event, Kiora, survived a shipwreck off the coast of Cape Town in 1899 and was found standing on a rock near the wreck site. Kiora fell at fence No. 5 during the race.

But back to the story. Gollan was a product of Hawke's Bay, where he was born at Mangatarata, near Waipukurau, in 1860. He was an only child after his mother, a widowed countess, died 15 days after his birth. His father, Donald Gollan, a Scottish surveyor with the New Zealand Company who arrived in 1841, bought a 30,000-acre estate at Mangatarate, near Waipukurau, and later dabbled in breeding and gave eight-year-old Spencer Gollan his first horse, which he named Chummy. While Gollan held Chummy in lifelong affection, he wasn't a horse he raced on.

His father moved into New Zealand politics, serving as East Coast's representative in the Wellington Provincial Council in 1857. He ensured his son enjoyed the best education, starting out in New Zealand before attending a finishing school in Switzerland that prepared him for Cambridge University. The proximity of the Newmarket racecourse ensured Gollan Junior further developed his interest in the equine game.

Returned to New Zealand, Gollan's first winning ride was on a mount named Liberty over a mile and a quarter at Waipukurau. It is an irony, though given the smallness of the racing industry in New Zealand at the time not unexpected, that Liberty's main rival in the race was a horse named Denbigh, the future dam of Moifaa. But Liberty won the race and his next two starts.

Gollan felt greater comfort in racing over the jumps. And that's where he concentrated his breeding efforts.

He struggled to succeed due to a string of mishaps with his horses, many of them suffering a gamut of accidents.

Typical in this regard was a two-year-old, Freda, he took to Flemington. But the field was so good he decided she wouldn't have a chance and went to lunch instead of watching her run. However, he was advised that his horse was leading during the race and rushed to see the finish.

That showing, and her subsequent form, saw him enter Freda for the Oaks and Derby a year later. But just before she was due to run the Oaks, she was spooked by a cat that got into her box. When the cat jumped in front of her, she slipped and fractured her pelvis. It resulted in further application of the phrase used to describe his misfortunes in the sport, 'Gollan's luck.'

He did have one famous mount before Moifaa, Tirailleur, by Musket out of Florence Macarthy, one of the finest horses seen in the era in Australia, winning all 10 three-year-old races he started, including the Great Northern Derby. Gollan went on to win a New Zealand Cup, a New Zealand Grand National, riding Norton to victory in 1894, a Canterbury Cup, the Hawke's Bay Guineas and Wanganui Derby, and in Australia, the Sydney Derby and Oaks, All-Aged Stakes, a Randwick Plate, the Melbourne Oaks and St. Leger.

The following year, he was a favourite to take the Melbourne Cup, but Tirailleur was knocked over during the race, broke his shoulder, and had to be put down. 'Gollan's luck strikes again.'

However, he wasn't always the victim of bad luck. After Tirailleur won the New Zealand Cup in 1889, Gollan was the recipient of a significant amount of cash from bookmakers. He was handed 900 pounds before catching the ferry from Lyttelton to Wellington. In his cabin, Gollan placed the rolls of notes in his top hat, which he locked in his hat-box. After arriving in Wellington, he discovered that all his travelling effects, including his hat-box, had not been taken to his hotel as was arranged. In the meantime, the steamer had sailed for Sydney.

Gollan walked to the offices of the Union Steamship Company. He asked if they could wire to Sydney for the return of a hat box by the next steamer. This was done, and after receipt of the hat box on the next steamer, he opened the box to find everything, including all his 900 pounds, where it should have been.

Gollan inherited a fortune after his father's death, aged 76, in 1887 and invested heavily in the best possible bloodstock. One of his successes was Bonnie Scotland, the second New Zealand-bred winner of the AJC Derby in 1894.

But a year later, he upped and moved to England, taking several horses with him. However, he had few successes before acquiring Moifaa.

Moifaa, a son of Natator and Denbigh, was sent to him by his half-brother, a son of his deceased mother. He did not immediately impact the English scene, his best result being a third in the Mole Handicap Steeplechase at Sandown. But as the Badminton Magazine said,

The Liverpool [Grand National] was his next outing, and nothing like confidence was felt – Mr Gollan thought what he had was a good jumper's chance, and it was no doubt his capacity in this direction that won him the race, for he gained the best part of two lengths at every fence, and, nicely handled by [jockey] Birch, as Turf history records, won by eight lengths from Kirkland, who was giving him three pounds.

He started at the long odds of 25 to 1, and a few good judges backed him because they had been struck by the style in which he went at the three jumps that come close together on the Sandown Course.[1]

The impression Moifaa made on the racing public was summed up by one Irishman who witnessed his triumph.

We think Ireland has horses that can 'lep', but I never saw one that could 'lep' like this one![2]

The King's Horse Ambush II was the favourite for the event. However, the Waipawa Mail's London Correspondent said it was likely two-thirds of the spectators would have lost interest in the event after Ambush 'blundered listlessly over two fences, fell heavily at the third – a five-foot fence with a five-foot ditch on the take-off side – and then walked quietly home'.

The field glasses were shut up, and silence fell, and amid a scene of utter indifference, three outsiders, whom a few spectators looked up on their cards and found to be The Gunner, Moifaa and Kirkland, came right away from the others and ran a very fine and unusually fast run race home, Moifaa drawing away and under a vigorous application of the whip winning at last fairly easily.[3]

Sydney's Daily Telegraph summed up the Australasian feelings raised by Gollan's success at Aintree.

That gentleman is easily the most representative of all Australasian sportsmen in England and it is doubtful if a better all-round sport is to be found anywhere. During his lengthy residence in New Zealand, where he still has some large squatting interests, Mr Gollan bred and raced a number of good horses, and frequentlours were seen both in Sydney and Melbourne...Mr Gollan is not only a racing man; he is an all-round sportsman with but few equals. He is an amateur sculler of a very high order, a champion at golf, and by no means a novice with boxing gloves, while as an amateur rider and a billiardist, he has frequently left his mark.[4]

Soon after his Aintree success, Gollan was approached by a livestock buyer of some renown, Lord Marcus Beresford, with an offer to buy Moifaa. After a sale was completed, Gollan learned Moifaa was bought by the King. Sadly, he never reproduced his winning form, and while favoured in the 1905 Grand National, he was one of 20 horses in the 27-team field that fell at fences.

However, with Australian Star, Gollan won the Sandown Grand Prize, City and Suburban and two Coronation Cups, while other horses, Ebor and Norton, won steeplechase events and The Bemkin and Saxon won hurdles races.

Gollan's sporting instincts revealed themselves when he believed it was worth pursuing the record for rowing from Oxford to Putney in London. The time stood at 16 hours by six Guardsmen who raced on the river before locks were installed. Gollan called on the services of professional scullers – Towns from Australia and fellow New Zealander Tom Sullivan, who was the English professional sculling champion a few years earlier. Gollan was responsible for getting Sullivan to compete in English rowing.

Again, the Badminton Magazine noted,

After a certain amount of practice, the trio started with three pairs of sculls, and Mr Gollan accomplished what he describes as the hardest day's work he had ever done in his life. Sullivan was so far from fit that he lost 16 lb [pounds] on the journey, but though slightly delirious, fifteen miles from home, finished well. The three struggled on, and including the tedious waits [at the locks], finally reached their destination in 13 hours 15 min.[5]

He was an ardent supporter of pure amateurism in sport.

He does not favour the Australian democratic trend towards quasi-professionalism in cricket, football, rowing, running, or any other athletic exercise. He says that rowing in England is conducted on sound lines, but once the working-man element was let into it the deterioration of the standard of amateurism would commence.[6]

The question of professionalism in sport is one that is going to reach a climax in the Homeland very shortly, and the people who will be responsible for the debacle will be the tennis players, being the most flagrant examples of professionals posing as amateurs.

I am still wondering how the Australian cricketers had the nerve to walk out of the amateur gateway of the pavilions during their last tour when the professional members of the team they were playing used the professional gateway. The Melbourne Argus, in a leader some time ago, said that there had not been an Australian amateur cricketer for many years, and I quite believe the statement.[7]

Yet, when asked about why British golfers struggled to beat American players he said,

The reason why the British golfer cannot beat the American is because he does not adopt the methods of training which the American brings into his golf as into every other sport.

"Golf is not a young man's game, and it looks bad to see great strapping young fellows doing a round a day and spending the rest of the day in the clubhouse, smoking cigarettes and imbibing too much alcohol in many cases. I'm afraid I was regarded as too outspoken in one case, at least.

"I was asked my opinion of a team of Oxford golfers, who I happened to meet in the course of my travels. I stated that they were doubtless very fine golfers, and if they found that they were rabbits at more energetic sports, such as Rugby football, they were doing the right thing to stick to the game.[8]

And while enamoured of amateurism in sport he served as match referee when New Zealand professional sculler Dick Arnst retained his world singles championship from Englishman Ernest Barry in his challenge on the Zambesi River near the Victorian Falls in 1910. Gollan was on his way back to England after a visit to New Zealand.

As a rowing coach, he coached his son Donald, a single sculler, who, despite partial deafness and having to communicate with sign language, was selected to row for Britain in its eight for the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, which finished second to the USA.

In 1925, aged 70, Gollan senior convinced the handicap marker at St Andrews in Scotland that he should be given a 14 handicap for the annual Queen Victoria Jubilee Vase tournament. By this stage, Gollan was blind in one eye due to an accident when the spiked point of a tree branch penetrated the pupil of an eye. It didn't help that he had an injured wrist during the event, having been struck a round or two before the tournament with a golf ball.

Mr Gollan, a tall, soldierly-looking man, as straight as a gun barrel, has triumphed over all the plus and scratch men at the Royal and Ancient Club who assemble at St. Andrews to battle for 'the jug' and other of the club's trophies...It is no joke for a man of 70, and handicapped by physical disabilities, to play eight consecutive rounds of the championship links, in a tearing wind that had never ceased blowing for the past four days.[9]

Mr Gollan had a large handicap, but we, we read, a very tired man when he holed the last putt to win, on the sixteenth green, the handsome trophy and the large sweepstakes which went with it. The winner, as was only natural, received a mighty cheer on his performance, for he must have proved himself a sportsman to his fingertips.[10]

Bernard Darwin, the legendary golf writer of the era felt that as a player who was still strong and hard, Gollan was generously treated by the handicappers.

Still, it was a great win, for even Mr Gollan, tough as he is, must have grown very, very weary. Moreover, his golf was a true pleasure to watch, for his best strokes, played often at critical moments and right through a raging wind, bore the hallmark of real class and might have made anybody jealous. His striking of the ball with an iron was beautifully crisp, clean and firm. What a lesson he taught, or ought to have taught, many of us in the arts of standing still or not trying to hit the cover off the ball and playing for position on a course where position is of supreme importance.[11]

The blindness in one eye was mentioned in a Coroner's Court report as a potential factor in his death when he was hit by a bus on Oxford Street in London on January 29, 1934.

The Badminton Magazine summed up the impression Gollan made during his years in Britain:

If the Colonies contain many such sportsmen, the Old Country has reason to be proud of its offspring.[12]

[1] Badminton Magazine, England, January 1906

[2] ibid

[3] Home Correspondent, Waipawa Mail, 12 May 1904

[4] Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 28 March 1904

[5] ibid

[6] Spencer Gollan, Sportsman on Tour, Wanganui Herald, 25 July 1910

[7] Gollan, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 5 February 1927

[8] Gollan, ibid

[9] 'Mr Greenwood', quoted in Referee, (Sydney), 18, November 1925

[10] 'Auld Reekie', Referee (Sydney), 18 November 1925.

[11] Bernard Darwin, Country Life, 12 September 1925

[12] Mr Spencer Gollan, Badminton Magazine, London, January 1906