Mark Nicholls' best pre-WWII XV

Former All Blacks five-eighths Mark Nicholls was one of the few players, Billy Stead was another, who took to rugby writing once his playing career was over.

Nicholls wrote a column for Auckland's Weekly News at the same time he was an All Blacks selector in 1937. That would never happen nowadays, but even in those heavily amateur times, he got away with it.

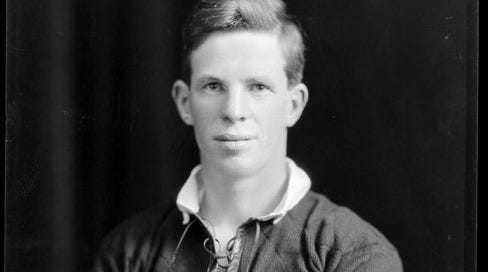

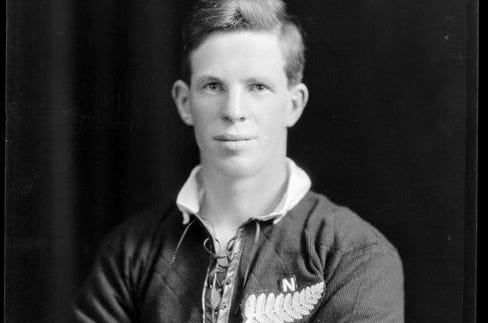

Mark Nicholls (Archives New Zealand Reference: ACGO 8333 IA1 1349 15/11/17721)

By 1939, the New Zealand Listener was being published weekly and Nicholls featured prominently, although it may have been because he regularly spoke on the emerging radio programmes of the era. Those pages are now available on New Zealand's newspaper and magazine archive Papers Past.

As one part of his radio lectures he proffered his opinion on a World XV based on pre-World War Two experiences, always a handy exercise for debate.

Starting from fullback, he couldn't separate Ireland's Ernie Crawford, South Africa's Gerard Morkel and his All Blacks team mate George Nepia, but writing for a New Zealand audience he said Nepia was his man. But if he had been Irish, he would have gone for Crawford, and South African, he would have selected Morkel.

He did say Springbok Gerry Brand was the best kicking fullback he saw, although he did recall Nepia's ability in that regard, in the lost first Test against the touring British & Irish Lions of 1930 played in Dunedin.

The Listener said Nicholls pointed out in his lecture,

From play on New Zealand's goal line, Nepia found touch at halfway. From the lineout, he was given a penalty kick and found touch two yards short of England's [sic] goal line. With a wet and heavy ball, he had covered the length of the field with two kicks.

Nicholls believed that others might have been more consistently accurate, but Nepia's kicking covered such great distances that no return could hope to make up the ground he gained.[1]

Nicholls next assessed wings, noting his belief that a wing should never give away possession. When receiving the ball, a wing's role was to make for the line with all his effort.

Only when he was absolutely certain that it would be advantageous should he kick. In preference, he should go down with the ball when tackled, and retain the ground won at all costs.[2]

The first wing to impress him was a star of the 1919 Kiwi Army team in South Africa Percy Storey. He shone against Wellington also, when returning from the 1920 tour to Australia with the All Blacks.

But in 1921, while in Dunedin preparing for the first Test against the South Africans, Nicholls saw them play Otago where W.C. 'Bill' Zeller's hat-trick was crucial for winning what he said was, 'one of the hardest and roughest matches I have seen.'[3]

Attie van Heerden, Henry Morkel, Jack Slater and D.O. Williams were other Springboks to impress him. On the Invincibles tour of 1924-25, England wings Cliff Gibbs and Richard Hamilton-Wicks stood out. Gibbs was the fastest wing he saw, but speed was all he had.

Twice he ran round the All Black defence and each time he gave away possession by kicking when he reached Nepia.[4]

Hamilton-Wicks scored a spectacular try for England when taking advantage of Bert Cooke being caught on the blindside, leaving an overlap he took advantage of.

Harry Stephenson for Ireland, and the Australian Johnny Wallace, who played for Oxford University were other overseas wings of note while Gus Hart and George Hart, Bill Elvey, Harry Svenson and Jack Steel were the best New Zealanders along with Storey.

Nicholls eventually plumped for West Coaster Steel for one wing.

He was one of the greatest wing three-quarters in the last 20 years – a fend like the kick of a mule – a capable scorer from anywhere on the field – a powerful punt.[5]

His other choice will surprise, French wing Adolphe Jaureguy.

A great player, a great theorist, and a great captain. He did more for French rugby than any other player. By producing him French Rugby (FFR) justified itself.[6]

Jaureguy led his side to wings over England, Scotland, Ireland and France at a time when the French were the least favoured side in the Five Nations.

At centre, Nicholls chose Scotsman G.P.S. 'Phil' McPherson.

McPherson was as swift and as graceful as a gazelle, but with none of the gazelle's timidity. He was one of the two or three hardest tacklers in post-World War 1 rugby.[7]

Nicholls said when seeing McPherson, who debuted for Scotland at 19, play in the annual Oxford-Cambridge game at Twickenham, he had seen a master in action.

Fellow New Zealander, dual international, All Blacks captain, and Rhodes Scholar, George Aitken, who partnered McPherson in the Scottish team, deserved special mention as did Sid Carlton who Nicholls said was the best defender of any All Blacks centre.

Choosing five-eighths, and leaving himself out of the equation, Nicholls opted for a combination of South African Bennie Osler and All Black Bert Cooke.

Bennie Osler had the hands and the speed, could punt, drop and place kick, was a master tactician, a match-winner, and a great rugby footballer. In 1928, the South African backs were by no means outstanding, but Osler managed to play a lone-handed game.

His playing methods naturally attracted the public's eye. Had Osler not played in 1928, Nicholls thought it highly probable that New Zealand would have won all four Tests.[8]

Cooke, from 1924-30, dominated the second five-eighths and centre positions in the New Zealand game.

He was terrifically fast off the mark, had wonderfully good hands, a fine turn of speed, a remarkable swerve with changes of direction concealed until the very last minute, and he was unselfish to a degree. It was delightful to play outside him.[9]

One other who came into consideration was Karl Ifwerson. Nicholls said Ifwerson was ideally built, was an outstanding place-kicker and could bluff the best of opponents.

Of all the players in a side, Nicholls said halfbacks had the hardest job on the field.

No other position demands such a specialist, and no other position demands that the player must excel in so many things.[10]

He rated Englishman Cecil Kershaw in the top flight along with South Africans Danie Craven, Pierre de Villiers, Mannetjies Michau and 'Tappy' Townsend. There were several All Blacks of ability, Teddy Roberts, Charlie Brown, 'Ginger' Nicholls, Jimmy Mill, Bill Dalley, Frank Kilby, Merv Corner, Joey Sadler, Harry Simon, Eric Tindill and Charlie Saxton.

But he opted for Roberts.

I have never seen anyone with more wonderful hands. His fielding, anticipation, and catching were uncanny. He was never content simply to feed his backs from behind the scrum, but would follow the ball out and join in all attacking movements. He could jink, dummy, and swerve through a whole team. He was faster than he appeared, and could kick expertly. He was a real rugby genius.[11]

While forward play was not his area of expertise, Nicholls threw a more general rule over the pack, selecting them in one hit and noting that most of them played during the 1920s. He generalised in their placement, apart from Jan Lotz, the South African hooker. He was never headed in games against all the rugby-playing nations.

South African Boy Morkel and England's Wavell Wakefield were chosen as locks while Australian Aubrey Hodgson, and New Zealanders Maurice Brownlie, Moke Belliss, Hugh McLean and 'Ranji' Wilson rounded out the side.

Brownlie was probably the finest physical speciman I have ever seen. He had great strength, and could break clean through when he had taken the ball in the lineout. On the English tour he was at the top of his form. New Zealanders never saw him play as well. He was most at home in a hard, desperate game.[12]

Belliss was the fastest forward he saw while Wakefield was also a fine track athlete, excelling in sprints and hurdles and Andrew 'Son' White was the best dribbler of a ball.

[1] Mark Nicholls, NZ Listener, 1 September 1939

[2] Ibid, 8 September 1939

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

[6] ibid

[7] Nicholls, 15 September 1939

[8] Nicholls, 22 September 1939

[9] ibid

[10] Nicholls, 29 September 1939

[11] ibid

[12] Nicholls, 6 October 1939