Bobby Jones' example still a lesson for sport

1930 Grand Slam was triumph of application and resolve

Is there a better sports biography than Mark Frost’s The Grand Slam, the story of the man regarded as the finest golfer of them all – Bobby Jones?

A century ago, Jones, always an amateur, was in the final stages of completing the reconnaissance trip through the golf world that would set him up for the most remarkable period of dominance his game, and many others, had ever seen.

That was Jones’ feat in winning the British Open, the British Amateur, the US Open, and the US Amateur titles in 1930. At 28, Jones retired from the highest levels of golf and got on with his life, although forever venerated as a great, if not the greatest, to have played the game.

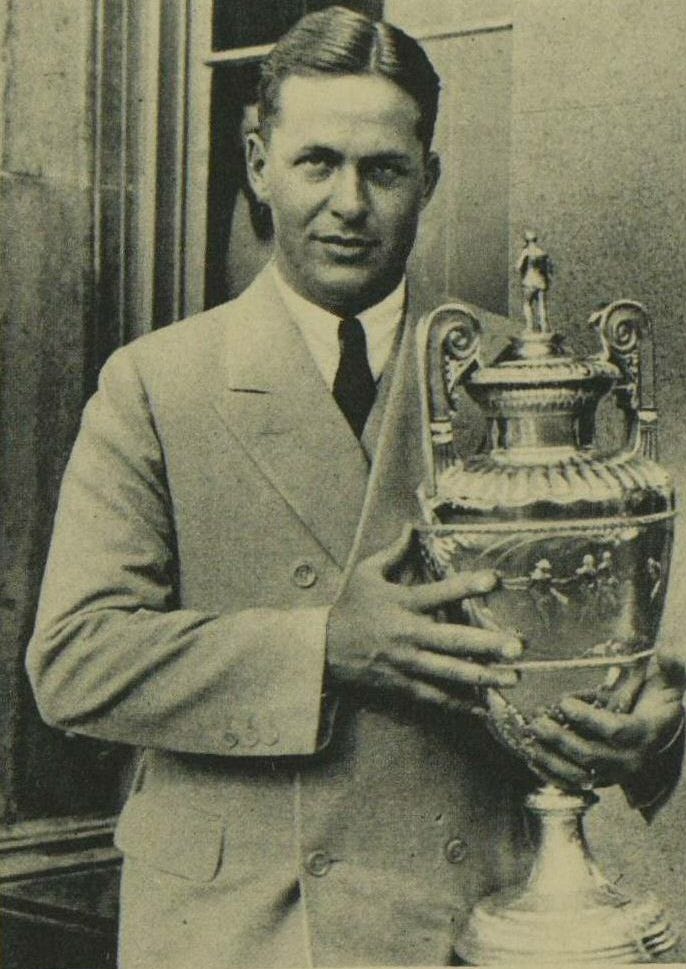

Bobby Jones with the trophy after winning the 1930 British Amateur Championship [Illustrated London News].

Frost completed his masterpiece in 2004, elevating it to the ranks of outstanding sports writing and earning recognition as one of the finest studies in the field.

A previously owned copy came this writer’s way recently, and it proved a riveting read. This is not just a record of outstanding success; it is a study of how a uniquely gifted player first came to appreciate the deficiencies in his make-up that threatened to impede his ability to achieve what he desired, and then sought to overcome them.

It is a tale as much about victory over some of the demanding golf layouts in the world, as it is about succeeding against deficiencies of purpose that allowed the little man on his shoulder to rule the roost, too often impeding the flow of commonsense from the brain to the levers of his body by which he had the ability to dominate games.

This was a player who had indulged in tantrums, who had so insulted the game when picking up his ball during a horror round and walking off the course, not just any course but the venerated Old Course at St Andrews. As natural as his ability may have seemed, Jones could still be reminded that he was as mortal as any other player, especially before big games, where he was prone to sleep-deprived nights due to nerves.

Because he was an amateur, who eventually found the legal education that offered him a productive career when his playing days were over, he was not a regular competitor in tournaments. University study provided a balance to the competitive streak, which could be addressed once qualifications were achieved.

That is what makes Bobby Jones’s transformation all the more memorable.

Of all the sportswriters of his generation, Grantland Rice was among those closest to Jones. Rice was a long-time friend of Jones’ father.

Rice wrote,

From 1917 to 1923, seven long years, Bob Jones went to war with his temperament...his eagerness to be perfect. He won that war but only after seven years of disappointment during which time he kept losing to opponents to whom he could spot several shots. Jones was 21 years old before he had himself conquered and could apply full concentration to the act of hitting a golf ball correctly.[1]

At 12 years, Jones could hit his drives 240-250 yards and he competed in his first US Amateur Championship aged 14½.

But the ability to come through under pressure, when the blue chips are down, is the sternest mark of The Champion.[2]

Jones told Rice,

I’ve suffered at this game a lot of years. Among other things, I’ve discovered a man must play golf by ‘feel’...the hardest thing in the world to describe - the hardest thing in the world to sense – when you have it completely...Today I have it completely. I don’t have to think of anything, just meet the ball.[3]

In more recent times, he might have described that as ‘being in the zone’.

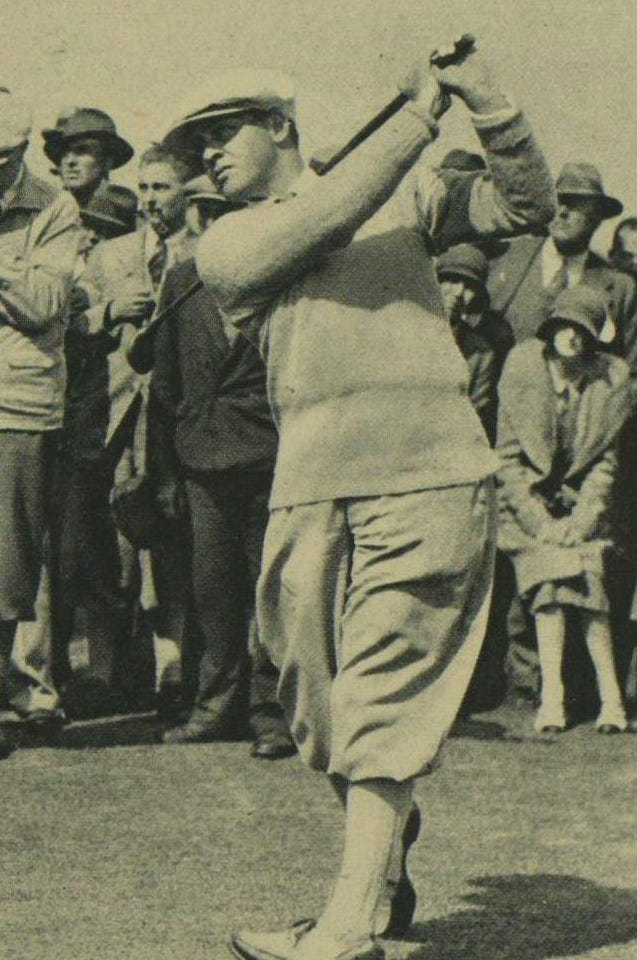

Bobby Jones drives during the 1930 Walker Cup tournament. [Illustrated London News].

Another writer of the era, Paul Gallico, arrived on the scene a little later, but his opinions align with Rice.

He was the finest golfer and competitor ever produced in the United States or anywhere else, the King himself of the Golden People.

...of all those I met and knew during my fourteen years as a sportswriter, spanning 1922 through 1936, [Jones] impressed me as being the best sportsman, the greatest gentleman, and the champion of champions.[4]

Gallico said Jones’ impact reflected the times of emerging post-World War One affluence which was undone by the economic collapse of 1929 that became the Great Depression.

...golf was a game that everyone of every age could play. It had been blessed by the doctors and was healthful. One did not have to be endowed with muscles or more than ordinary co-ordination. In the playing of it, one was not hit, stabbed, bruised, or knocked down and, best of all, the ball was not thrown.[5]

We were Jones and Jones was us, because all through his career he was the only one who really behaved like the ordinary, everyday golfer who attended to his job and played at weekends.[6]

Gallico drew on a comment Rice made in a 1940 article to explain the uniqueness of Bobby Jones.

There is no more chance that golf will give the world another Jones than there is that literature will produce another Shakespeare, sculpture another Phidias, music another Chopin. There is no more probability that the next five hundred years will produce another Bob than there is that two human beings will be born with identical fingerprints.[7]

By dint of sheer hard work, Frost, the author of The Greatest Game Ever Played, has scoured the archives, spoken with survivors, and pieced together a highly readable account. Frost described Jones’ childhood and the influences that came together to produce the quality player he became.

The coverage of his significant tournaments is comprehensive, with impressive breakdowns of his opponents and how they played their matches, which contribute to the fullness of the story. Blended with the play are the social events of the day, which provide an in-depth understanding of the era in which Jones’ results were achieved.

They were different times, but that doesn’t make them any less meaningful.

Typical of his approach to the game, and that of Americans of the times, was their unfamiliarity with the links courses of Britain, especially Scotland. He started out with a love-hate relationship with the old course at St Andrews. At the British Open of 1921, he came to grief on the 11th hole of the third round and failed to finish his round, ripping up his card to disqualify himself. While he played his fourth round, he left with Scots followers with a diminished view of his ability.

But, in an example of how he dealt with a burr under his saddle, Jones worked out what playing the old course was about, and how it had to be treated.

By the time he arrived in Scotland for the 1927 Open, he told the Manchester Guardian,

I consider St. Andrews the most attractive golf course I have ever played over, and if I fail next week I shall not blame it on the old course.[8]

That was borne out in his 68 in the first round of 1927 in the Open – par was 73, and he tied the course record. It was the first time he broke 70 in any of the Opens he played. It demonstrated that he had come to appreciate its challenges. And, after winning the Open on the Old Course, he asked that the Royal and Ancient Golf Club retain the trophy rather than have him take it home to Atlanta.

Cyril Tolley, the British amateur champion in 1920 and 1929, said the 1927 Open was ‘the most amazing in the long history of the event.’ And Jones’ dominance of it stemmed from his approach shots to the green.

That shot has proved one of the master shots in Jones’s armoury, but he was great in all departments. His driving was not only spectacular by reason of its prodigious length, but because of the marvellous accuracy in placing. There lay one of the secrets of the great golfer’s triumph, for placing the drives at St. Andrews on the chosen spots opens the gateway. The champion’s putting was beautifully controlled, for the greens at St. Andrews, always fast, had, comparatively speaking, a stubbly surface and were treacherous in that they, were fast in some places and slow in others.[9]

Frost described Jones’ epiphany regarding the course.

Since his first visit to St. Andrews six years before, Bob had schooled himself in the traditions of the Auld Grey Toon and embraced them as a student of the game. He had also grown to love and appreciate the nearby course that started it all...The genius of the Old Course lies not in its inherent difficulty but in the overwhelming number of options it presents a golfer. Standing on the tee, you are seldom if ever directed to follow any specific part to the green; what more often confronts you is a flat, featureless landscape – alive with hidden dangers – through which you must carefully plot your way. With its seven huge double greens – some of them over an acre in size – varied pin positions, and the infinitely changeable wind, you are almost never asked to play the same course twice. The Old Course requires great skill, but more than that, it demands precise thinking and strategy; you first beat this golf course with your mind by creating a disciplined plan of attack, one shot setting up the next as if in a chess game, and then you have to go out and execute it...Talent, nerve, a relentless mentality: not many players had all these weapons in their arsenal. It was no wonder that by his third trip to St. Andrews, Bob had decided that this primal testing ground where the game had taken root represented the greatest challenge golf had to offer.[10]

Bobby Jones clears from a the Cottage bunker during the British Amateur of 1930. [Illustrated London News].

And it was at St Andrews that his 1930 Slam began when he won the British Amateur. Including a double eagle two on the fourth hold courtesy of a long shot from a bunker, that ensured his connection with the course and township was completely rehabilitated. When adding the Open title that allowed his Grand Slam pursuit to continue in the USA, Jones would later say,

These two British championships were the hardest of any I could remember. I might say they still are.[11]

Scottish admiration for him was emphasised when in Scotland en route to the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, his request to play a private round resulted in the township of St. Andrews closing up with 6000 turning up at the course to witness Jones’ round of 71, and hear him comment that he had played the round as well as any he had played in his life.[12]

And while he is still regarded as the greatest player of all, it was not a notion he believed.

I think we must agree that all a man can do is beat the people who are around at the same time he is. He cannot win from those who came before any more than he can from those who come afterward. It is grossly unfair to anyone who takes pride in his record to see it compared to those of other players who have been competing in some different period against entirely different people under wholly different conditions.[13]

That’s not to forget other basic considerations to impede comparisons.

The first thing to point out is that there is nothing absolute about scoring in golf. We all know that the same golf course can change, even from day to day, depending upon weather conditions. Furthermore, over the longer range there has been a steady improvement in the conditioning of our better golf courses. Artificial watering has lead to a greater consistency in the turf of fairways and greens, weed control has given us the means of eraticating clover, crab grass and a good many other course pests which often prevented the clean contact between club and ball so vital to control of iron shots. On a properly conditioned course today, it is almost impossible to get a bad lie.[14]

And that is before considerations in the changes in balls and clubs are taken into consideration. They had made the game easier. Jones also felt a significant psychological barrier, akin to breaking the four-minute mile, had occurred.

In my day every player set out in an open championship with some sort of feeling – often well defined – that he had to have at least one bad round. There was even, a saying to the effect that ‘those who do not blow up in the third round will in the fourth.’[15]

Jones attributed that breakthrough to Ralph Guldahl in 1938 and 1938.

Ralph made it clear that in order to win you had to play four good rounds, not just three. It has been that way ever since, and that difference of four to seven strokes accounts for most of the improvement in championship scoring since the ‘30s.[16]

It was after he retired that he became a professional, something he felt was necessary when asked to make a series of coaching films for general release. He also helped design a set of irons bearing his name, although he had played with hickory clubs all his competitive career. Among his lasting legacies, and one that linked him to the game through the years, was his involvement in developing the course at Augusta, which eventually saw the US Masters become the fourth Major in the modern game.

Always a revered figure, he refused to reduce his commitments to the game after being diagnosed with a rare neurological condition known as syringomyelia, which resulted in him being unable to walk in his later years. He died in 1971, aged 69, one of the most revered of all sportsmen.

[1] Grantland Rice, The Tumult and the Shouting, Dell Sports, New York 1954

[2] ibid

[3] ibid

[4] Paul Gallico, The Golden People, Doubleday and Coy, New York 1964

[5] ibid

[6] ibid

[7] Gallico, quoting Grantland Rice, ibid

[8] Bobby Jones, Manchester Guardian, 5 July 1927

[9] Cyril Tolley, Manchester Guardian, 16 July 1927

[10] Mark Frost, The Grand Slam, Hyperion, New York, 2004

[11] Robert Tyre Jones Jr, Sports Illustrated, 14 November 1960

[12] Frost ibid

[13] Robert Tyre Jones Jr, Sports Illustrated, 7 November 1960

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ibid