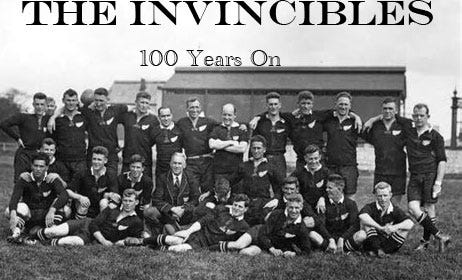

Arriving in England, the All Blacks knew that comparisons of them and their predecessors of 1905-06, the Originals, were inevitable, especially since Devon would be the opening game.

When the Originals opened up against England's champion county on their tour, they rocked the nation with a 55-4 win. Devon was regarded as the weakest of the English sides when Cliff Porter's men lined up for their game.

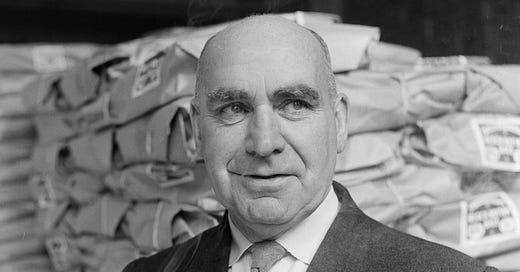

After they managed an 11-0 win, tour manager Stan Dean commented:

If this is the weakest county in England, then we are in for a very hot time![1]

For the home team, this game marked the beginning of their season on September 13. They were determined to avoid the embarrassment their fathers suffered nearly 20 years earlier. Their efforts were bolstered by the inclusion of the Scottish international, J.C. Buchanan, who delivered a truly outstanding performance in the lineouts and showcased exceptional dribbling skills.

At one point in the second half, Nicholls said that Buchanan dribbled the ball more than 70 yards. However, Nepia showed his anticipation skills by driving the Scotsman towards the sideline, where he secured the ball, eluded the defence and found touch in Devon's 25 area.

But the real issue for the All Blacks came from their 2-3-2 scrum. They were a complete failure.

We tried for the loose head but Devon resisted our every attempt. If we got it, they swung the scrum round or prevented the ball from being put in. On one occasion, seven attempts were made to get the ball fairly into the scrum. This continual scrummaging got to the bottom of our chaps, who at this time were not real scrummagers, and the Devon forwards gradually assumed the upper hand. If there was one thing we did not expect, it was the failure of our forwards, However, if they failed in scrummaging, they were superior in speed and ability to handle, two factors that in later games enabled them to add materially to the score.[2]

Halfback Bill Dalley said there wasn't a decent scrum all day. The refereeing of Mr. M. Roberts proved poor, and he refused to award a clear dropped goal by Cliff Porter. He also denied Alf West a try 20 minutes into the game but didn't say why. R.A. Barr said the referee also failed to penalise the Devon players for not letting go of the ball after being tackled.

Wet weather did not help. The ground was heavy, but the ability of the All Blacks backs was decisive. Ginger Nicholls felt Devon set out to be spoilers.

They played seven men in the scrums, the other forward playing as extra five-eighth, the halfback doing wing-forward work, marking Porter, and throwing the ball in the scrums and lineouts. The halfback here had a lot to put up with. The All Blacks attacked during the major portion of the first half, but lacked the usual dash amongst the forwards. Time and again they would break through the Devon defence, only to be called back for offside or knock-on.[3]

But not all was doom and gloom. Former Press reporter A.J. Harrop was studying at Oxford and covered several games of the tour. He didn't share the despondency some of the touring New Zealand journalists felt.

I am convinced that the All Blacks will score freely against a large number of opposing sides...The All Blacks will have to improve vastly to win any of the internationals, but there is no doubt in my mind that they will improve vastly on yesterday's showing. They have the attributes of speed and determination which are essential to success.[4]

The All Blacks showed what they could do after a failed Devon penalty goal attempt from halfway. The ball hit the crossbar, and the New Zealanders secured the ball. When Bert Cooke raced ahead with the ball, he sent a long pass to Svenson. Taking the ball at top speed, he raced for the line, but just short delivered a perfect reverse pass to Cooke, who scored a try in what Harrop said was one of the best movements he had seen while in England.

An unnamed New Zealand writer [probably E.E. Booth] criticised Devon for its back play still being in the 'Dark Ages'. There was far too much short-line kicking and little attacking intent.

Where is the cutting in, the reverse and in-pass from the outside wing, keeping the attacking movement flung swiftly to the final lines, the open and dazzling play of the All Blacks rearguard?[5]

English rugby might have been of a higher standard than in 1905-06, but the game was still stereotypical, he said. Long passes were lobbed to the centre, straight across the field, with no pressure at attempting to cross the advantage line. Wings couldn't run freely and were jammed against the touchlines. As long as English teams played a crossfield game, they were unlikely to beat any touring team from New Zealand.

Scorers: All Blacks 11 (K Svenson, B Cooke, H Brown tries; G Nepia con) Devon 0. HT: 8-0. Referee: R.A. Roberts, NZ touch judge J.H. Parker

However, the All Blacks were rattled at their inability to dominate Devon. Mark Nicholls said they returned to their base at Newton Abbot 'sadly bewildered.'

It was unanimously decided that we would have to forego the fight for the loose head in the scrum. We had attempted to pack down on the outside man of their front row, a move which would have given us, when it was our ball, first hook at the ball and a more than even chance of obtaining possession. Naturally our opponents did not intend to allow us any such advantage, and the manoeuvring to gain this loose head resulted in, what one critic described it, 'a dog fight'. So, for the remainder of the tour, we allowed our opponents the loose head in every scrum, which was tantamount to giving them possession. This was a disadvantage which no team should be able to overcome consistently, and that we did overcome it was not owing to any particular genius that we may have possessed, but because of the utter lack of tactical skill on the part of our opponents. This handicap alone was sufficient to prevent any comparison between us and our predecessors of 1905, for they packed on the outside man and were allowed to do so, and their getting possession of the ball from almost every scrummage were enabled to play the game as they wanted to, whereas we very often had to play the game as our opponents decreed.[6]

The news was better on the wing-forward front. Dai Gent said Cliff Porter was not the curiosity Dave Gallaher had been in 1905. Porter thus found it more difficult to shine in the way Gallaher had. Gent also noted there didn't appear to be a Charlie Seeling in the pack, but Jock Richardson and Maurice Brownlie were good in the open without the grace or dash or handling powers of Seeling. Billy Stead and Jimmy Hunter had been significant pivots in 1905, and Cooke, with his corkscrew runs, reminded him of Hunter, always making ground and worrying his opponents.

It is very early to compare the team as a unit with its predecessors, and some weeks must elapse before they shake down and form a real combination used to one another's tactics, and, what is more important, used to their opponents' tactics, but there was certainly far less cohesion today on the New Zealand side than was the case in the same match in 1905. But do not let me be misunderstood; none of this is to belittle our visitors. They follow a great side, the greatest I have seen, and I believe they will train on into a very useful team indeed, with far more victories than defeats to their credit, for they are keen, young and capable. All I want to convey is that I was not so impressed at this stage as I was with the last New Zealand team.[7]

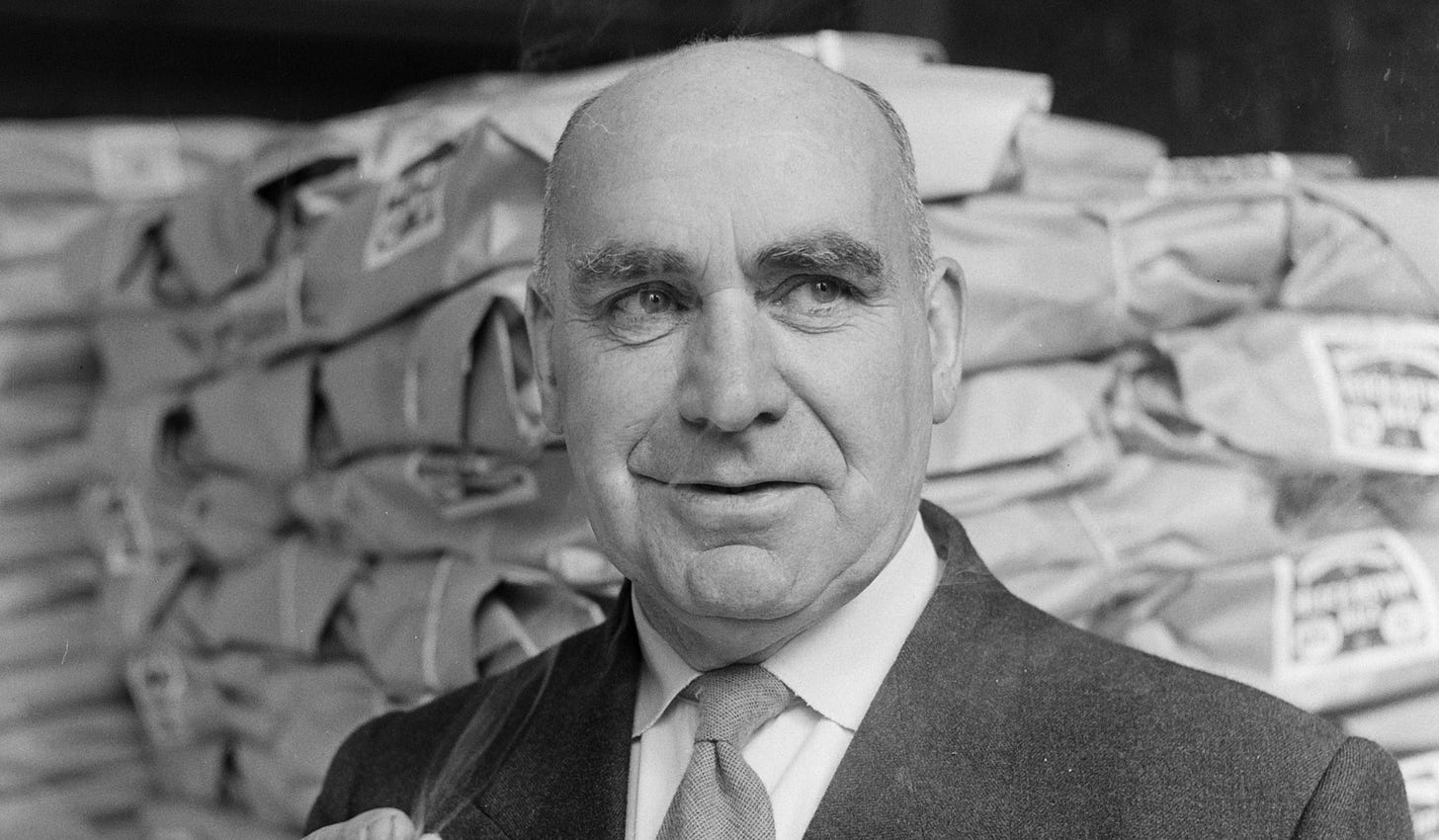

The prominent sports journalist of the era, Colonel Philip Trevor, said the All Blacks, despite not having shown their best form, shaped as a capable and dangerous attacking combination who were 'scrupulously fair' and played a clean game. Trevor had a long association with New Zealand rugby.

Towards the close of the Boer War, in 1902, there was an armistice. I was serving at the time in the army operating in Natal, and Headquarters then were in the little township of Newcastle. There were gathered there some 20,000 mounted infantry, all from New Zealand, Australia and Canada. It was discovered that in the New Zealand and Australian contingents there were roughly about two dozen men who were what we call internationals, so a kind of impromptu miniature international match was arranged, and I refereed it. The Australians did well enough, but the New Zealanders, playing superbly, gained a great victory. Their performance was an eye-opener to me, and their speed (which, by the way, is not the same thing as pace) showed me a kind of play I had never seen, and I pondered these things. I stayed on in the Army two years, then I retired, returned home, and resumed my journalistic work. When, in the summer of 1905, the great tour of the All Blacks was announced, I wrote in the Press: 'The New Zealanders are coming, and we shall never see the way they go.'

Trevor was criticised for his comments by his readers, but he took the attitude that he laughs longest who laughed last.

Cliff Porter - ‘Always in the right place’

So far as scrummaging issues were concerned in the tour's early stages, he said the 2-3-2 formation was ideal for getting fast ball, if it was done precisely. That hadn't been the case against Devon. He was intrigued by the change in the style of wing-forward play shown by Porter.

I have often seen a rover in action before, and I have on these occasions found him to be a better friend to the other side than to his own. That was not the case in this game, when Porter...played rover. In both attack and defence he was always in the right place, and never in the wrong one. He is in obvious charge of the policy of the team.[8]

NEXT ISSUE: More rain, more frustrations

[1] Mark Nicholls, Weekly News, 11 September 1935

[2] Nicholls, ibid

[3] Ginger Nicholls, New Zealand Free Lance, With the All Blacks 2, 29 October 1924

[4] A J Harrop, The Press, 29 October 1924

[5] A New Zealander, The Observer, 23 September 1924

[6] Mark Nicholls, Weekly News, 18 September 1935

[7] Dai Gent, Sunday Times, 14 September 1924

[8] Col. Philip Trevor, Daily Telegraph, 15 September 1924