Reflections of the 1924-25 Invincibles tour have highlighted how fortunate the side was in avoiding significant injuries to their leading players and yet were successful despite the high number of games played by their leading performers.

Members of the 1905-06 Originals had warned of staleness in the latter stages that would result if relying too much on their best players. But somehow, the 1924-25 All Blacks got it right.

That had unfortunate consequences for those players who lost form or could not get a run of games when coming back from injuries, but there appears to have been a genuine willingness to contribute to the cause.

The end result is not only an unbeaten team but also one free of the rancour that can occur on tour and one where the application of superior skills overcame every challenge.

British journalist Denzil Batchelor believed the stars of the show were: Mark Nicholls, George Nepia, Gus Hart, Bert Cooke, 'Snowy' Svenson, Jim Parker, the Brownlie brothers, Maurice and Cyril, and Jock Richardson. And he said,

Only one team of overseas footballers ever played an entire season of Rugby across England, Ireland, Wales and France, winning every single one of the thirty matches in which it was engaged. That team was the New Zealand side of 1925...I put my hand on my heart when I assure you that it would have taken thirty points off any Rugby XV we have seen at Twickenham since world [sic] War II.[1]

And the reason they succeeeded, he said, was

...because they were better at geometry, because they could work out fresh plans of attack for a petrifying conventional game. Yes, they won because they were strategists in an age when great players insisted, in the British tradition, on playing Rugby by numbers. It is strange how the English resent any fresh tactics in the game their fathers taught them.[2]

Their quality marked them as superior. Some assessments of those involved follows.

George Nepia holds a revered place in All Blacks history, the first superstar in the game being lauded as the finest player in the fullback position in the world, and impressing with his stamina in playing every game on the tour. British critics lined up to eulogise his play. A.J. Harrop said,

One of the brightest memories of the great tour will be that of Nepia taking the ball at full-speed and finding touch far down the field.[3]

Batchelor, reflecting on sports memories during his career, rated Nepia 'the towering personality' of the side. He had repaid every ounce of faith placed on him with selection as the sole fullback.

He was between short and tall, and his thighs were like young tree trunks. His head was fit for the prow of a Viking Longship, with its passionless, sculped bronzed features and plume of blue-black hair. Behind the game he slunk from side to side like a black panther on the prowl; but not like a black panther behind bars – like a lord of the jungle on the prowl for a kill...His long, low-angled kicking, especially of a heavy ball, was a miracle of accuracy and length. His punts raked the touch lines. A third of the length of the field was the average he liked to maintain.[4]

Nepia was denied the chance to contribute to his nine-Test legacy by being excluded from the 1928 tour of South Africa because of his race. As with all pre-1992 visits to South Africa, the 1928 event deserves an asterisk to acknowledge New Zealand was not at full strength. He was frustrated when injured touring Australia in 1929 when he had hoped to better demonstrate to locals that he was a better player than who toured in 1924. He returned to the All Blacks to play the British in 1930 and should have been included in the 1935-36 touring team. Rugby's loss was league's gain as he took up a contract in England before returning to play league for New Zealand. His final first-class rugby game was in 1947, and he was also a first-class referee. A farmer, he died in 1986 aged 81.

Bert Cooke played 23 games on tour, playing in each of the four Tests, eight at centre and 15 at second five-eighths, and scored 19 tries. Arthur Carman said,

Looking back, one recollects his sudden and quick break through, his snappy run, his timely and useful short punt. He passes well on all occasions, and gives those who back him up every opportunity. Without a doubt, however, his greatest attributes were his dash and quickness off the mark, added, of course, to quick thinking, or rather sharp instinct.[5]

And A.J. Harrop added,

Cooke achieved lasting fame in Rugby history during the tour. His lightning dashes, quick following-up, and genius for seizing an opening place him on a level with the greatest. In the English match he was closely marked owing to the team being short of a man, but his sound defence was conspicuous.[6]

Batchelor said Cooke, especially when paired with Nicholls, was 'the most dangerous scoring force on the field that season.'[7]

Cliff Porter may have missed the selection for three of the Tests on the tour, but there was no doubt that the team appreciated his contribution. He received a special presentation from the side at the tour's end, and years later, players to a man who said he was the best leader they ever had. Arthur Carman noted,

The success of the tour resulted largely from Porter's successful captaincy off the field, and he never spared himself in working for the good of the side. I cannot imaging a more ideal skipper for a touring team, and his choice for that position, was an extremely fortunate one in the circumstances.[8]

His play suffered because of the administrative load he was forced to bear when manager Stan Dean failed in core duties, and it wasn't until the last Test in France that he received recognition. There was a clash of wing-forward style with Jim Parker, but Porter suffered an injury at the wrong time. He played seven Tests in his career, missing the tour to South Africa but captaining the side against New South Wales in New Zealand in 1925 and 1928 and to Australia in 1929. He led them against the British in 1930, the year he retired from playing. He was lost to administration, having declared to his side that he would never be involved in the game's management as long as Dean was involved. A printing company manager, he died in 1976, aged 77.

Vice-captain Jock Richardson retired after the tour, having played in seven Tests. Arthur Carman said Richardson was one of the successful players on tour, playing in each Test match. But he placed him behind Morrie Brownlie, Son White and Bill Irvine as the leading forwards.

The reason was that for the latter part of the tour, Richardson fell away somewhat, and did not put the work in that a forward should. He showed signs of developing into a 'shiner', but made a great return to his old style of play in the final game at Toulouse.[9]

He played his last first-class game for Southland in 1926. An accountant, he was appointed in 1927 as the Southland Rugby Union's secretary until the mid-1930s. He was also secretary of the Southland Boxing Association. He left Southland under a financial cloud in the mid-1930s and lived on the south coast of New South Wales for the remainder of his life. He died aged 95.

Of all the forwards on the tour, flanker Maurice Brownlie emerged with the finest reputation. A player regarded by his rivals as the greatest opponent they faced, he was strong and a powerful presence in the pack.

Morrie is so effective in securing possession of the ball for his side, from the lineout or the loose, and he was invariably one of the hardest working and most conscientious forwards in the team. He took the tour very seriously, and was so well trainted that he several times was in danger of going 'stale'.

One often wonders how Morrie keeps going as he does, as he uses far more strength than most players. He seems to have acquited the ability to apply every ounce of strength he possesses.[10]

He played eight Tests in his career and captained the All Blacks to South Africa in 1928, having first come on the scene playing for Hawke's Bay against the 1921 Springbok tourists. He retired in 1930 having played against the touring British side for Hawke's Bay. A farmer, he did in 1957 aged 59.

Cyril Brownlie was three inches taller than brother Maurice, and a stone heavier, and was unfortunate in being sent off in the tour finale against England. It took him time to get into top form on tour, he played only five of the first 15 games. But from that point he was involved in all the crucial games. Carman offered a new thought on his dismissal in the England game.

It is admitted that the game was a bit 'wild', and play was furious for a start, but without any real 'dirt' as far as could be seen. Ten minutes from the start, near the New Zealand line, Cyril got the ball, but dropped it, though [Reg] Edwards then rushed and grappled him (thinking Cyril still had the ball). The two struggled for a minute, and then Edwards went flying over, and Cyril turned around to join a scrum only to be told to leave the field. Not a soul in the press box knew what had happened to cause him to be sent off, and many refused to believe that he really had been ordered off. No one in the press box (of over 30 pressmen), saw Cyril kick Edwards, and I leave it at that.[11]

However, it wasn't the end of his career as he was selected to tour South Africa in 1928, but injury restricted him to only six games and they were his last for New Zealand. He played three Tests and, like Maurice, he retired after the 1930 season. A farmer, he died in 1954 aged 58.

It is surprising in retrospect that first five-eighths Mark Nicholls was not among the front runners for selection in the All Blacks touring side. He was not among the first or second five-eighths selected to play against New South Wales in 1923 and was regarded lucky to be selected for the trials process. Arthur Carman said that was probably due to the lack of classy five-eighths available. He made the most of his chances and was included among the certainties.

Carman added he was 'the most useful and sound man in the backs.'

Batchelor described his approach,

Nicholls, with his twenty yards spurt, in which the brain moved faster than the invisibly swift feet, charted the enemy's order of battle and probed the chink.[12]

It was his misfortune to suffer injuries that kept him out of half the games, but he managed to be available when most required, which was all four Tests and the games against Swansea, Newport, Leicester, Cumberland, Ulster and the university sides of Cambridge and Oxford.

There was also the praise from Wisden that his 'conduct of operations in the five-eighths position, showed a conception of the New Zealand game that amounted to genius.'

He only played seven games on tour at first five-eighths and nine at second five-eighths. That was due to issues at centre that necessitated playing Bert Cooke there, while there was also the discovery that Neil McGregor was more than capable of handling the first five-eighths role, giving it a degree of defensive strength that Nicholls could not match.

Nicholls continued to play until 1931, featuring on the tour of South Africa in 1928, albeit playing only the fourth Test in which his contribution saw the series drawn, and against the British tourists of 1930. He became a Wellington and All Blacks selector and was a columnist for the Weekly News from 1936-39. He died in 1972, aged 70.

It seems astounding nowadays that Les Cupples, a player crucial to the 1924-25 Invincibles pack, should only have played 41 first-class games, six of them Tests. He came to light when playing for Bay of Plenty against the 1921 Springboks – they rated him 'the best forward in New Zealand'. But Bay of Plenty did not play many games in a season. So, All Blacks selection came late to him; a First World War veteran with the New Zealand Medical Corps, he was awarded a Military Medal for his life-saving actions at Gravenstafel. But while playing in 17 games on the tour, including the Tests against Ireland and Wales, Carman was dismissive of his contribution.

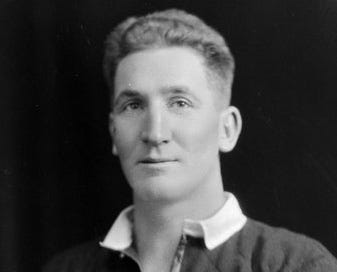

Les Cupples (Archives New Zealand Reference: ACGO 8333 IA1 1349 15/11/17721)

In each case [the Tests] his place was secured owing to another man's bad luck. [Ron] Stewart in the first instance, and [Son] White in the second, having to withdraw owing to illness and injuries...Cupples played well, consistently, but in my opinion was not of sufficient class.[13]

It was a harsh comment. Plenty of replacements have been tried and failed, Les Cupples didn't. He retired after the 1924-25 tour and farmed, dying in 1972 at 74 years.

Centre Handley Brown struggled for regular game time on the tour and wasn't able to break into the Test side as a result of Bert Cooke moving out to centre. Harrop said his inability to rise to occasions was one of the few disappointments of the tour.

He played several sound games, but did not develop sufficient thrust to qualify for the centre position in the international games.[14]

He did tour again, with the 1926 All Blacks to Australia, but played only two of the eight games, one of them at fullback. He retired after completing 49 games for Taranaki at the end of the 1930 season. A timber merchant, he died in 1973 aged 69.

Wairarapa stalwart Quentin Donald played in all four Tests of the Invincibles tour but was not selected for the All Blacks again. He made his provincial debut in 1918, straight out of Wellington College, and his North Island debut a year later, aged 19, but played only spasmodically for the next three years. He carried a heavy workload on the tour after Abe Munro's injury and because Brian McCleary did not reach his best form.

Donald's greatest attribute is his quickness in the tight to open up the play, his ability to use his feet well and the fact that besides Maurice Brownlie, he was the best tackler among the forwards.[15]

Donald suffered frustrating illnesses, including pneumonia, that restricted his play in 1925-26. Sometimes, he played in the backs to get onto the field. Donald played 48 games for his province before retiring in 1928. He died in 1965, aged 65.

'Gus' Hart played only 29 first-class games, 17 of them on the 1924-25 tour upon which he was the highest try scorer. Unknown nationally before the side was selected, he was among the first chosen to make the tour when appearing for the North Island in the annual inter-island game. Hart had the sheer speed to benefit from Bert Cooke's breaks through the midfield to score three tries, leaving the more experienced Jack Steel in his wake. He performed exceptionally well in the games in the north of England, scoring 15 tries in five games and ending as the highest try scorer with 20 on the tour.

He proved a most valuable member of the team and with a little luck would have been in the first XV right through the tour – Steel didn't beat him by much...On the small side, he was extremely fast. His openings had to be made for him, but his great pace enabled him to finish off an attack splendidly.[16]

He played intermittently until injury forced his retirement in 1926, a career of 28 first-class games, only seven of them for Taranaki, but achieved 33 tries. He died in 1965 aged 67.

Bill 'Bull' Irvine made his New Zealand debut in the third 'Test' of 1923 and performed well enough through the trials in 1924 to be included among the 16 certainties first named to tour.

On the tour, Irvine more than fulfilled expectations, and it is not too much to say that none of the players were more consistent and reliable than 'Bill' Irvine. He played in 27 of the 30 matches. That was down to the injury suffered by Abe Munro and the poor form of Brian McCleary.

What the team would have done without him in the circumstances it is hard to say, the poor play of McCleary throwing all the work on to Donald and Irvine. Only Irvine's great stamina could have enabled him to keep up under the strain of continuous play.

Touring referee with the side, Len Simpson wrote of a try Irvine scored against Wales.

Irvine's second try will never be forgotten by the 50,000 spectators. New Zealand were defending when suddenly Cooke broke through with the ball at his toe, and one of the most brilliant dribbling rushes ever seen took place, the ball being passed beautifully from player to player by at least eight New Zealanders, forwards and backs joining in, and finishing with Irvine scoring a sensational try.[17]

He toured played NSW in 1925 and toured Australia in 1926. He played five Tests in his career which ended in 1930 after 32 games for Hawke's Bay and 31 games for Wairarapa. He died in 1952, aged 53, having been a publican after retiring from New Zealand's Permanent Forces.

Centre Fred Lucas enjoyed a seven-Test career and was among the Invincibles who also toured South Africa in 1928. He had an indifferent start to the 1924-25 tour and conceded his specialist position of centre through the early stages to wing Snowy Svenson. Yet he was named at centre for the first Test against Ireland, a game in which he played below par. At one stage, he was dropped for four games, and it wasn't until near tour's end against Combined Services that he produced the sort of performance expected of him.

It was a game out of the box, and showed of what he was capable. Straight running, confidence and safe handling were his assets that day, and he scored three tries himself, with men waiting for passes, so completely had the defence been beaten.[18]

Yet, it was a fleeting performance as he fell into his old ways in the next game. Across his career he played 48 times for Auckland before playing four Tests against the British in 1930 after which he retired. He died aged 55 in 1957.

Lock Read Masters was another who retired after the Invincibles returned home. He played all four Tests on the tour. His main rival, Ian Harvey, ran into illness issues both on the Australian leg when he suffered influenza and then in Britain, where he fell victim to tonsilitis that hospitalised him, causing him to miss 18 games. Masters took up the slack, being rested only once in Harvey's absence.

He was a key scrummager as the lock in the 2-3-2 scrum.

Masters was a good honest forward, always ready to take his part in all that was on, and too much praise cannot be given him for the able manner in which he held a responsible position, at the time when so much depended on him. He was always dependable and never played a poor game.[19]

Illness forced his early retirement from rugby in 1925. He became a Canterbury selector and was a New Zealand selector in 1949, also serving as president of the NZRU in 1955. He wrote a book on the tour, With the All Blacks in Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia 1924-25, and was one of the original editors of the New Zealand Rugby Almanack. He died in 1967, 10 days after New Zealand Rugby's 75th Jubilee, aged 66.

First five-eighths Neil McGregor was another who toured South Africa in 1928 but injury confined him to four games. The Wales and England Tests of the Invincibles tour were his only Test matches. Bill Dalley rated his play. "When he was playing the game, he never gave up...he was one of the best tacklers in the game when I was playing."[20]

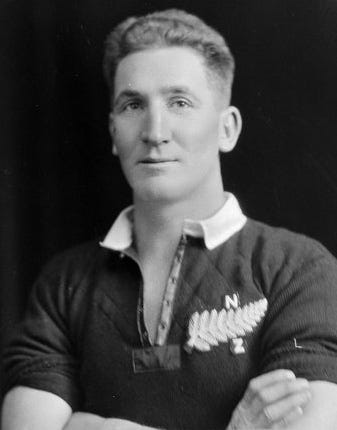

Neil McGregor

Harrop said,

While many reputations were consolidated during the tour, McGregor's became definitely established. Harsh things were said of him before the tour began, but they cannot be said now. In the gruelling contests against Cambridge, Wales and England, McGregor proved himself a marvel in defence. He faced forward rushes with unflinching valour all the more praiseworthy, as every match imposes a great nervous strain on him.[21]

He retired after the 1928 tour and worked for the New Zealand Customs Department. He coached and selected the Christchurch club, and then in Nelson, later in his life, he coached the Nelson provincial side and was a South Island selector. He died aged 71 in 1973.

Halfback Jimmy Mill's determination to play a higher class of rugby than was available at Tokomaru Bay saw him migrate south to Hawke's Bay for the winter of 1923, and he claimed a place on the touring side.

By the end of the tour, Carman said he became one of New Zealand's most outstanding halves.

At first he had to take second place to Dalley, but, steadily improving, he was soon recognised as a great all-round halfback. Speedy, resourceful and nippy, he was ever eager to open up the play, and very seldom spoiled chances by holding on to the ball. He was, moreover, particularly dangerous at a scrum anywhere near the line, and scored several tries by his great burst through, a great piece of work being his try under the posts in the match against Cambridge Varsity on a muddy ground, and which N.Z. only won 5-0.[22]

First five-eighths Neil McGregor said of Mill,

I haven't seen a halfback since so fast in movement, one who judged so well the time to run, even if it were only two or three yards, or one who had such a 'hesitation' side step which he could use both ways. He was a great attacking half.[23]

And the Evening Post noted of him,

The great feature of Jimmy Mill's halfback play was his brilliance on the blind side. As elusive as an eel, he foiled his opponents not so much by swerving or sidestepping as by propping, a trick he could execute with the most baffling results. Even opponents who thought that they knew every trick he possessed were always liable to be fooled.[24]

And Harrop said that while his early form was disappointing he reached his best form at the critical stages by playing some brilliant games.

In the English match he performed a double duty, in Cyril Brownlie's absence, with conspicuous success.[25]Denied a place on the 1928 South Africa tour on race grounds, he completed his career with four Tests, retiring in 1930. Mill died in 1950, aged 50

Andrew 'Son' White was the second to oldest player in the side but that did not hold him back. He played 21 of the 30 games. All but one of his games was played at the back of the scrum, this despite his being the shortest player, apart from the hookers, in the team.

'Son' never played a poor game and generally he was one of the two best men in the pack. His experience, well-applied weight, expertness as a dribbler, and the fact that he never shirked the tight work, rather did he revel in it, more than counterbalanced disadvantages of weight and height – which disadvantages are, as a matter of fact, forgotten when thinking of 'Son' White...White's form never failed, and his best games were towards the end of the tour.[26]

White moved to Christchurch and played for the Christchurch club in 1927 but retired at the end of the season. A storeman, he died in 1968 aged 74.

Lui Paewai debuted for the All Blacks as a 19-year-old in 1923 in the final game against the touring New South Wales side and won over the critics as the best first five-eighths seen in Wellington that season. While selected for the tour in 1924, Paewai and fellow five-eighths Ces Badeley suffered because while two players were selected to cover other positions, five five-eighths were included for the two positions available.

Carman said his best tour showing was in the 42-4 win over Yorkshire when the backs showed great combination, and while many of the tries scored were the result of Paewai breaks, he was too often inclined to run too far with the ball.

His greatest fault was his individualism, which got him nowhere, and left his backs standing in a line exasperatingly waiting for the ball, which did not appear. He was quick and nippy on attack, but weak on defence, and altogether failed to reach the required standard. He was young, and a coach might have made all the difference, had there been one with the team.[27]

Paewai returned to play for Hawke's Bay. In 1927, he transferred to Auckland where he played 12 games before retiring in 1928. He died at 63 years in 1970.

Wing-forward Jim Parker served in Palestine in the First World War, at one stage playing in a rugby game in the same team as the Brownlies and Jock Richardson. Back in New Zealand, he varied between playing in the three-quarters or the pack. He missed the 1921-22 seasons due to a recurrence of malaria first suffered during the war. In 1923, he settled more into the wing-forward role, for which he was selected on the touring side. He played so well in his 16 tour games that Carman regarded him as one of the successes. Carman said it wasn't possible to compare Parker and his rival, captain Cliff Porter.

They are players of wildly differing styles, and Porter has played games such as Parker could never play, whilst the same applies to Parker...Jim Parker, there is no doubt, made a success of his play – he suited the conditions better, and was of great value to the team.[28]

Parker retired in 1925 and became a key figure in the orchard industry, later becoming the chairman of the Apple and Pear Marketing Board. He died in 1980, aged 83.

Wing Jack Steel, New Zealand's player of the series against South Africa in 1921, had to play his way back into the side in 1924, having been regarded as 'over the hill' at the age of 25. But he stamped himself on the trials and was included among the 16 certainties. However, an injury on the voyage to England meant he didn't start playing until the fifth game, and it was not until after the Ireland Test, where he was not selected, that he started to find his best form. He finished with 18 tries in 16 games without having achieved the level of play he was renowned for in New Zealand. Wisden said of him,

Steel, a heavily-built man, possessed a fine turn of speed, and was the strongest runner of the three-quarters, but one could praise his resolution more if he had not so often used his weight in a manner not quite in accord with the best traditions of the Rugby game.[29]

After the tour, he played his seventh consecutive game for the South Island, a record. He continued to play until 1929, his last first-class games being for Canterbury. A railwayman, he died in a car accident in 1941 aged 42.

Alf West was the oldest player, at 31 years, selected for the tour and was the solitary member of the New Zealand Army team that won the King's Cup in 1919. He toured Australia with the All Blacks in 1920 and the second and third Tests against South Africa in 1921. He returned to the All Blacks in 1923 against NSW and then gained a place on the touring side. However, he played only 10 games and had an issue with catching colds.

West was an exceptionally good forward in the lineout, and was in this respect useful, but he lacked the necessary dash and vigour that was required, and that combined with the fact of his not being well part of the time, resulted in his receiving so few games.[30]

Morrie Mackenzie said Alf West was an under-rated contributor to the touring side.

Both Cliff [Porter] and Jim Parker told me that they owed a lot to the tips given them by old hands like Alf West. Alf was a rough diamond with the heart of gold.[31]

Back in New Zealand, West played only one game for Taranaki in 1925, his last first-class appearance. West died in 1934 aged 40.

Alan Robilliard was from a family of provincial players; his father played for Canterbury, and his three sons played first-class games. Alan moved from Mid Canterbury to Christchurch in 1922 and was selected for his Canterbury debut a year later. An early trialist for the 1924 side, he was placed in the reserves for the second trial. He scored a brilliant try when replacing an injured player and was included in the South Island team. He faced the final trial to choose the final 13 tourists. Conditions were so bad that he gained his place by making the fewest mistakes.

He played only four games on tour, breaking his ankle in the second game. He didn't play again until the Cambridge game, and he also played against Oxford, where he scored his only try on the tour. But with the other wings doing so well, he got no more games. He played for ex-Toulousians against the ex-Basques the day before the French Test, along with Alf West, Brian McCleary and Jim Parker.

Youth favoured Robilliard, and he played for the All Blacks regularly until retiring after the 1928 tour of South Africa. He was a jeweller and died in Little Rakaia, aged 86.

A powerful player, Ron Stewart, was the 'baby' of the Invincibles side. He made his first-class debut in 1921 for South Canterbury at 17 years of age against the Springboks, yet his promise was evident when playing as a replacement during the 1922 inter-island game, which the South Island won 9-8. An inter-island start in the 6-6 draw saw him among the new players included in the third 'Test' against New South Wales in 1923. During the pre-tour trial process in 1924, he was one of the 16 certainties chosen.

Taking time to settle in, he played six consecutive games, culminating in his best display against Cumberland. Carman wrote,

In style of play and general fitness he resembled Morrie Brownlie more nearly than anyone else, and it was generally predicted after the Cumberland match that he would be the best forward in the team at the end of the tour.[32]

Unfortunately, he caught a cold in camp before the Ireland Test and was in hospital when the Test was played with pleurisy. While recovering to play against London Counties in their first game, in which he played outstandingly, he had returned too soon, and while rested afterwards, he did not recover and did not play again on the tour.

Stewart celebrated his 21st birthday when the All Blacks attended the Folies Bergere in Paris at the end of their tour, and while in Canada, Carman claimed he demonstrated his swimming ability by winning Canada's 100-yard freestyle title.

He continued to play after his return and did so well on the 1926 tour of Australia that when the team returned with many injuries, he played at fullback against Auckland.

Stewart toured South Africa in 1928, and when the All Blacks needed to change their 2-3-2 scrum to negate the Springbok advantage, it was Stewart who stepped up play in the front row to significant effect. His final Tests were those against the 1930 British and Irish tourists, injury forcing his retirement. Stewart was a selector of the 1945-46 Kiwis team. A stock agent, he became a director of J.E. Watson and Co. and was also a director of two newspaper companies. He also served on the Southland RFU management committee. He retired to Central Otago and died aged 78 in Queenstown.

K.S. 'Snowy' Svenson had been around the first-class scene since 1919 when he debuted for Wanganui and was selected for the North Island in 1921. He moved to Buller in 1922 and was selected for the South Island and also the New Zealand team that toured Australia. Illness prevented him playing on the tour, but he did play against Wellington before the tour and against the New Zealand Māori when the team returned.

In 1923 he played his rugby in Wellington alongside Cliff Porter for the Athletic club. In 1924, he retained the favour of the All Blacks selectors and on the pre-tour visit to Australia, he established a role on the wing, and on the British, Irish and French tour he played 21 of 30 games and scored 18 tries, including the first try of the tour, against Devon. He scored the winning try against Newport, and managed to score in each of the Tests.

Svenson proved himself one of the most reliable men in the team – quiet but consistent, always willing and always a worker who missed few opportunities. He was most dependable and held his place in the first fifteen as a wing three-quarter without any chance of being deposed by sheer merit. His trickiness on attack made up for lack of real speed, though quickness is as important as speed, and Svenson has that.[33]

Returning to New Zealand, he played for the All Blacks against the touring NSW team in 1925 and in 1926 toured Australia with the All Blacks. He retired at the end of the season. He died at Rotokauri, Raglan in 1955, aged 57.

Undeterred at being able to crack a permanent place in the Canterbury team between his debut in 1921 and 1923, Bill Dalley went into the 1924 season looking to do everything he could to tour with the All Blacks. In two South Island trials, he had the better of his main rival, Clarrie St George, although St George was named to play for the South Island. He dropped out of consideration on that display, and Dalley was named to start in the final trial, securing his tour place.

On the tour, he had the better start and was the preferred halfback up until the Ireland Test when his form declined.

He seemed to lose the extra bit of dash, and although still outstanding on defence, became stodgy on attack, and Mill, improving at every game, proved easily the better man. Mill had brilliance in attack, that few successful halves have, but Dalley was always the better man on defence, or when the game was a hard forward one on a heavy ground.[34]

Yet, a decision on who would play halfback against Wales was left until the final morning to check the conditions, and Mill got the nod.

The rivalry between the pair continued through the years after, touring Australia in 1926 and Dalley captaining Canterbury in provincial play. Due to not sending Māori to South Africa in 1928, Dalley thrived, especially after the other halfback Frank Kilby was injured. Dalley played in the four Tests. Injury interrupted his 1929 tour to Australia, and while a member of the Canterbury team that beat the 1930 British touring side, he was not selected for the Tests.

A traveller, Bill Dalley served as an administrator with Canterbury Rugby while also representing the province in bowls. He did in 1989, aged 87.

Front rower Brian McCleary made his provincial debut for Canterbury in 1920 but missed the 1921 and 1922 seasons. He returned in 1923, making the South Island side, and was selected to play NSW in the first 'Test' that year but had to pull out due to head injuries sustained while boxing. He was New Zealand heavyweight champion in 1920 and 1921, Australasian champion in 1921 and New Zealand professional heavyweight and light-heavyweight champion of New Zealand in 1923 until losing his titles to future world heavyweight contender Tom Heeney.

But in 1924, he came through the South Island trials and was selected for the inter-island game, doing well enough to be included among the certainties named for the tour.

His tour was disappointing. Arthur Carman wrote,

On the whole tour he played in but seven of the 30 games, and many were the reasons assigned to this by those who knew nothing of the position.

It was simply found that McCleary could not produce football of the class required – he seemed to have been chosen knowing very little of general rugby play, or else he was right off colour. Brian was one of the fittest men in the team, but out of the scrum he didn't appear to have the faintest conception of what to do with the ball when he received it, or as to what a forward should do. Even as a hooker, it must be stated that he showed very little knowledge of the position.[35]

McCleary played no more first-class games after the tour. He died in Martinborough in 1978, aged 81.

Wairarapa forward Ian Harvey had a circuitous route to All Blacks status. He debuted in the forwards as an 18-year-old against the Springboks in 1921, but in 1922, he played fullback. It was in 1923 that he settled in the forwards and, after going through the trial process, was named in the first 16 players selected for the 1924-25 tour.

The illnesses that marred his career saw him miss the pre-tour visit to Sydney, where he was taken from the boat to the hospital with influenza. He played four of the first five games in England and then developed tonsolitis. He had an operation, after which his throat became septic. He couldn't play until the 24th game and was far from fit. He played two other games, the last against a French XV, where he looked his fittest.

Carman said,

In the circumstances the All Blacks were fortunate in having a reliable man like Masters to fall back on, but I am giving nothing away when I state that Harvey was the better player of the two in all respects and with ordinary luck, should have developed into a champion.[36]

Illness prevented him playing back in New Zealand, in all but a club game, in 1925. He toured Australia with the All Blacks, but ended the tour with a cold and played no more that season. Selected for South Africa, he again succumbed to illness playing only four games, three of them at the end of the tour and including his solitary Test, in the fourth Test.

He continued to play for Wairarapa until 1930. A farmer, he died in 1966, aged 63.

A product of University rugby, due to studying in Christchurch as an engineer after returning from the First World War, 'Abe' Munro debuted for Canterbury in 1920, the same year he toured Australia with NZ Universities. He played in Canterbury's win over the 1921 Springboks but, from 1922, played for Otago. He made another NZ Universities tour to Australia in 1923 and, in 1924, was among the 16 certainties selected to tour Britain, Ireland and France.

On the pre-tour visit to Australia, he and Bill Irvine quickly formed a good front-row combination. Munro started well in England, playing the first three games, but against Leicester, he suffered a displaced cartilage in a knee that kept him out of the remainder of the tour.

While playing for Otago University after the tour, his knee collapsed, and he was forced to retire. He became involved in coaching and University rugby in his later years, dying at 77 in 1974.

Ces Badeley, the original captain of the 1924 side for their pre-tour visit to Australia, made his first appearance for Auckland in 1917, during the restricted age rugby of the war years. He served in France before returning to Auckland to play in 1919. In 1923, he achieved the unusual feat of playing for the South Island, having been selected for the North when injuries ran out for the South Island team.

Baddeley was returned to Auckland midway through the trials process for the 1924-25 tour, and many felt his chances were gone. But he was called back for the final trial and was included. Arthur Carman said the selectors appeared to have wanted Otago's Dr Arnold Perry as the captain of the side, but he failed to perform, and that was when they fell back to Badeley as leader.

He led the side in the first game against NSW, which the Sydneysiders won, and he was dropped for the remaining games.

His failure is hard to account for, but as one who saw the game, I can only say that he continually ran into the ruck with the ball, and lacked any sort of initiative, and displayed no sense of his duties as leader of the team, the side being hopelessly at sea the whole game.[37]

Badeley played in only two games on the tour, and that was down to one too many first five-eighths being selected.

I can't see how Badeley could have received many more games. Five five-eighths were too many, and on their play Badeley and Paewai were the weakest. The success of a team depends too much on the combination attained by the inside backs to keep shifting them around, and also there were remarkably few of the so-called 'easy' matches, in which to 'give players games.'

Badeley spent the 1927 season in Northland, playing for North Auckland, before returning to Auckland in 1927. A law clerk, he died in 1986, aged 90.

This concludes this centennial series of the 1924-25 Invincibles tour to Britain, Ireland, France and Canada.

[1] Denzil Batchelor, Days Without Sunset, Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1949, p.210-11

[2] Ibid, p.211

[3] A.J. Harrop, The Press, 24 February 1925

[4] Batchelor, ibid, p214-15

[5] Arthur Carman Daily Telegraph (Napier), 21 July 1927

[6] A.J. Harrop, ibid

[7] Batchlor, ibid 213

[8] Arthur Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 4 October 1927

[9] Carman ibid, 15 September 1927

[10] Arthur Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 20 September 1927

[11] Carman ibid, 8 September 1927

[12] Batchelor, ibid, p.213

[13] Carman, ibid

[14] Harrop ibid

[15] Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 23 June 1927

[16] Carman, ibid, 4 August 1927

[17] Lou Simpson, quoted by Arthur Carman, date unknown

[18] Carman, ibid, 30 August 1927

[19] Carman, ibid, 6 September 1927

[20] Bill Dalley, quoted in The Old Club, The History of the Christchurch Football Club 1863-2013, by Tony Murdoch, 2013.

[21] Harrop, ibid

[22] Arthur Carman, NZ Sportsman, 14 May 1927

[23] Neil McGregor, Sports Post, date unknown.

[24] Sports Editor, Evening Post, 30 March 1950

[25] Harrop ibid

[26] Arthur Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 21 May 1927

[27] Arthur Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 11 August 1927

[28] Carman, ibid, 28 July 1927

[29] Wisden Rugby Almanack, 1925

[30] Arthur Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 13 August 1927

[31] Morrie Mackenzie, Black, Black, Black, Minerva Publishing, Auckland 1969.

[32] A. Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 6 October 1927

[33] A.H. Carman, N.Z. Sportsman, 28 May 1927

[34] A.H. Carman, Daily Telegraph (Napier), 18 August 1927

[35] Carman, ibid, 27 September 1927

[36] Carman, ibid, 30 June 1927

[37] Carman, ibid, 25 August 1927