Outstanding as the Invincibles were completing their unbeaten tour, not all aspects of their game succeeded.

In many ways, the tour was the beginning of the end of the 2-3-2 scrum and the wing-forward. Mark Nicholls returned believing the 2-3-2 scrum had to go, and he was even more emphatic after the 1928 tour of South Africa.

But it was clear that the method of the All Blacks beyond those parts of the game gave a reminder to the Home countries that the lessons of the 1905-06 Originals had not been fully absorbed. A rundown of observations during the tour and at its end are included in this first of a two-part assessment of the tour's impact.

H.F. Crowther-Smith, in The Sketch, noted around the time of the Wales' Test,

One of the chief lessons that sticks out for us to sit up and take notice of in the game of the All Blacks is the value of speed. Not merely individual speed, but all-round, intensive quickness by every member of the team during every minute of the game – and then some. The average club in this country is satisfied if it has the luck to find a couple of players who won the 100 yards at school in something over 10 sec. Having made such a find, these two sprinters are put, as a matter of course, in the wing three-quarter positions, for, generally speaking, we cling to the idea that pace is not required in other departments of the game...

When the All Blacks are attacking, every man in the team is on his toes. Not merely speed of foot, as measured by the clock, characterises every movement, but, mentally, they are like lightning in deciding the nature and direction of the attack. And the man who starts it never hesitates that fatal fraction of a second as to what he is going to do with the ball. Neither does any member of the team hang about looking on.

Every one of the fifteen players moves at once in support of the other. The whole lot, forwards and all, seem to be transformed into three-quarters. The running is straight; the ball changes hands at a bewildering pace. And it is speed all the time on the part of everybody. In a flash, the opposition find their fullback faced with the ugly proposition of stopping three men (one with the ball) single-handed. The fullback, not being an octopus, a try between the posts is inevitable.

Every time I have seen the All Blacks attacking, I have been struck by the fact that their formation (seven forwards and five backs) is one that they turn to the best advantage. Our backs, because they find themselves opposed by two or three others, hesitate to go for the man with the ball, with the result that he makes considerable headway himself, can, 'sell the dummy' very readily, and often gets right away before passing to the various other players who are in close support.[1]

In the Liverpool Post and Mercury, V.A.S. Beanland, saw similar virtues relating to speed.

Where the New Zealanders were so over-whelmingly superior was in quick thinking, in the sureness of their handling, and in their wonderful backing up. They are essentially a team, a team in which, with very few exceptions, any man can play in any position. The objective is the opposing goal line, and that line is crossed chiefly by handling. And so every man knows how to pick up a rolling ball or to take a pass when at top speed...One has seen many more brilliant matches, but it is doubtful if any team of Great Britain or Ireland, since the war, could have beaten the 'All Blacks' as they played this afternoon.[2]

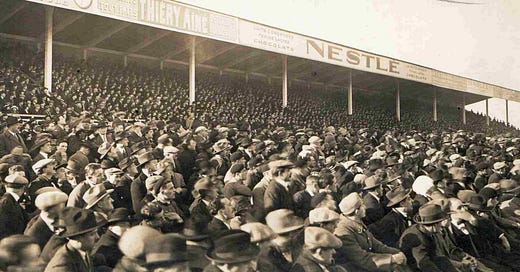

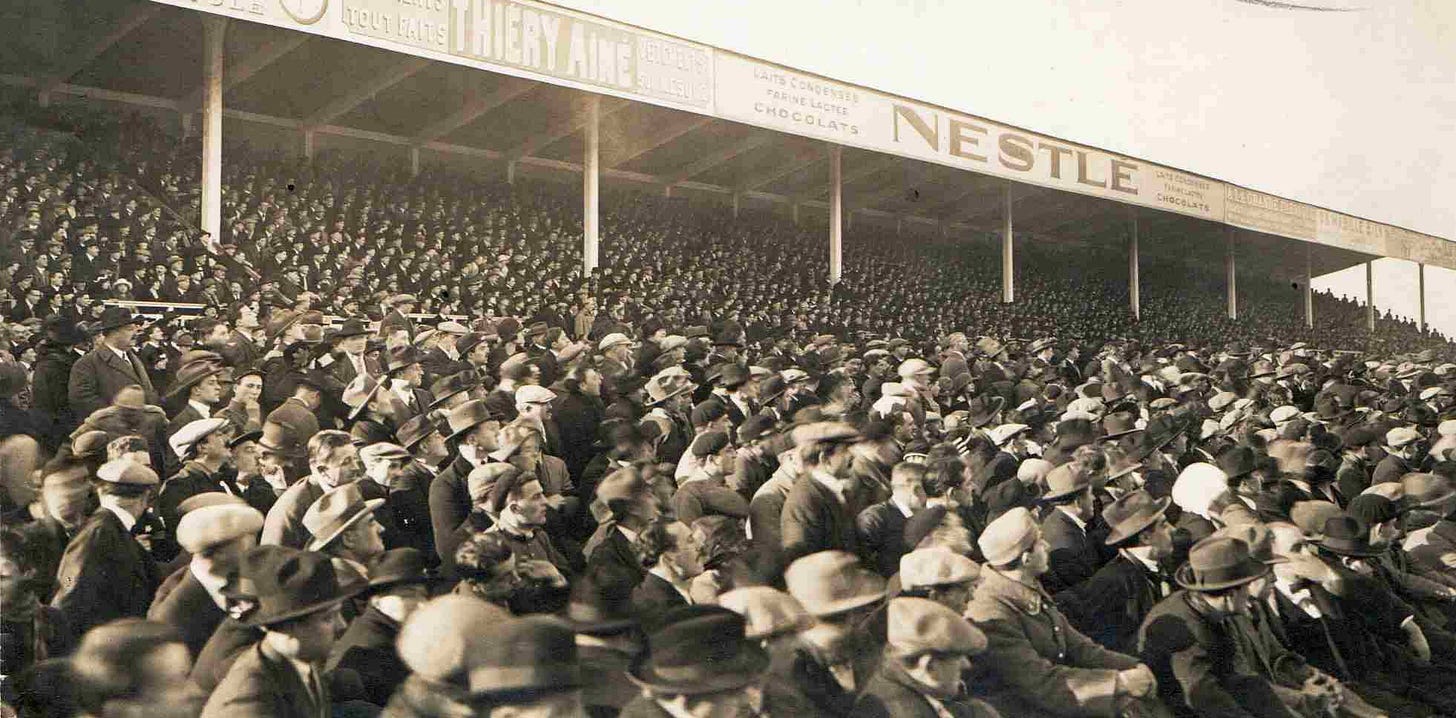

All eyes in Toulouse on the France v All Blacks Test action

Mark Nicholls has already made his feelings known about the writing of F.J. Sellicks, but in this magazine offering, Sellicks assessed why the All Blacks were so successful, even if not as good as Gallaher's men, in his mind.

The Welsh team of 1924 is a very different proposition from the Welsh side of 1905, and it needs a good idea of imagination to place the All Blacks of today at the same level as those of nineteen years ago.

Quite possibly, the All Blacks might have risen to greater heights had it been necessary to do so, but as things were, they were not called upon for a supreme effort. Wales were always slow and cumbersome; never at any moment were they inspired, as they sometimes have been, to achieve the unexpected. The one thing certain is that no side can hope to beat the All Blacks, which contains a single man who is not in the very acme of condition.[3]

Another writer had commented before the England Test, about the prospect of the All Blacks' style being handled by England.

Most of us think that this England side will see that the 'Luck of Twickenham' is preserved. England Rugby was never better than it is today; forward sciences, as applied to the game by W.W. Wakefield, brings out modernism at its best, and the materiel outside was never more luxurious. The Selectors cannot help doing well in their choice.

A good deal of nonsense has been written about deep strategy in the New Zealand game. The New Zealanders are just splendidly hard players, endowed with pace and every art of the game; they tackle, follow up, pass unerringly, and (a big conjunction this) – run straight. And the England side can do the same.[4]

As it turned out, the 2-3-2 scrum did poorly on the 1924-25 visit. It was frequently outplayed, and it was generally agreed that the All Blacks got only 30-40 per cent of their possession from the scrum over the tour.

Its love affair with and refusal to do away with the 2-3-2 caused massive debate following the 1924-25 tour and after 1931 when it was decided not to play it. New Zealand's scrummaging suffered for at least 25 years and possibly longer.

But what was the fuss all about?

Firstly, the wing-forward. Australian Rhodes Scholar and England international G.V. Portus wrote about rugby for the Sydney Mail. After the 1924 games, he recognised opponents' frustrations when attempting to contain the free-roving New Zealand wing-forward. Opposing breakaways had their hands full, keeping the wing-forward from disrupting their halfback. If they did their job, they could give their halfback three or four vital yards to get his backline away with an overlap.

It is of no use merely to lament the existence of a wing forward. There he is, and, keeping within the rules, he can make things very awkward for the other side, as [Cliff] Porter demonstrated very conclusively. After all, it may be said, this problem is not a general but a particular one. It may be urged that it is not the wing-forward that bothers us as a wing-forward, but it was Porter himself. I do not think I agree with this. I admit that Porter is a wonderful player – the best all-round man, I think, that New Zealand has sent us since the war. But I cannot see why any active, intelligent man with a good physique and a sure pair of hands (and the Dominion has many such) would not have proved a thorn in the side of the home defence in their last three matches. This problem of the wing-forward and the seven and eight packs is no new one, but the recent tour has certainly raised it again in an active way.[5]

The 1905-06 All Black Ernest E. Booth had taken to journalism after the tour, covering tours in Britain and Australia. He said the wing-forward was a blot on New Zealand's game. He wondered if those who played in the position or administrated the game ever realised what overseas rugby people felt about the position.

After a long and varied experience in both England and Australia, I can state with some assurity that the continued playing of this position is viewed as a species of stiff-necked parochialism, provincial egotism, seemingly a fetish and New Zealand copyright.[6]

New Zealanders liked to offer thoughts on what needed to happen in the game's laws yet continued to defy the world with their flawed wing-forward thinking.

We in New Zealand seem to forget that the moral idea differs in various countries. By persisting in playing practice or custom, which will be pronounced unfair in another country, we adopt a bad policy. New Zealand is again foisting upon New South Wales and Britain a custom that does not tend towards harmonious play, and that will be most prejudicial to the team itself both in action and off the field.[7]

Booth said after the constant abuse the late Dave Gallaher went through in 1905, New Zealand should have dropped the wing-forward concept.

The Rugby world can assimilate and understand the 'vulgar fraction' (five-eighths) theory in New Zealand play, but the continuance of the wing forward is not generally considered as worthy of such champions as the New Zealanders. It is generally expected on this tour it will be played in a very much modified manner.[8]

Yet Arthur Carman, who covered the Invincibles' tour with contracts for several New Zealand newspapers, said New Zealand's advance in rugby was because players were never satisfied with things as they were. They always looked for ways to improve the game they loved, and it was because of the success of their experiments that New Zealand became the pre-eminent rugby country of the world. When that incentive to experiment was missing, the game soon started to deteriorate.

One of the greatest experiments was the wing forward.

Ever since T.R. Ellison originated the innovation of taking players from the scrum and calling them wing forwards, this position has been the most criticised of any. Perhaps, had the player been called a rover, it mightn't have been so bad; but as it is the position that has brought upon its holders all the criticism and abuse of which its opponents were capable. And it matters not who might be the wing forward at the time, the criticism has been levelled at the position rather than the man himself.[9]

Carman said because of the prejudice against the 'terrible wing forwards' during the 1905 tour, [Gallaher and George Gillett] those who played in the position on the 1924-25 tour were watched far more by referees and fans than players in other positions. Because of the roving nature of the wing forward, he was not confined to a particular style of plan. Some felt they needed to keep as close to the scrum as possible to protect their halfback from unfair interference, or they should harass the opposing halfback at every opportunity. Others saw themselves as fast 'terriers' getting out among opposing backs to upset their continuity. Or they could play the extra man in their backline.

The rules [sic-laws] of Rugby provide for 15 players aside and it is left to the captains to decide how they shall be played; and, provided the spirit of the game is preserved, there is no reason at all against the seven scrum and the wing-forward.

"It is true that with hookers of equal ability on each side, and with the weight properly applied, eight men will secure more of the ball than seven; but the side with seven men has the advantag (when they do secure the ball) of an extra man on attack. Should the other side secure, the wing forward will be quickly on their half or five-eighths to upset the movement, and so the extra roving forward can offset the advantage gained.

But then we have gained, in that we have developed the open style of forward play with our forwards good in the loose, fast and good handlers.[10]

Carman said tight forward play, with old-time scrummagers, was not enjoyable to players or spectators. Difficulties for the Invincibles arose when they met forwards with scrummaging ability. New Zealand teams found in 1924, and it was repeated fours years later in South Africa, that their loose forward play could not hold its own because the scrum work of British and African packs demanded an equal competition between eight on each side. It was also a fact that there were usually twice as many scrums in Britain and South Africa as in New Zealand.

However, compared to Gallaher's wing forward of 1905-06, Porter had a different style. Porter was,

A master of anticipation, eagerly following the run of play; on attack, initiating numerous movements by snapping up mistakes by the opposition; on defence, a very hand extra defence.[11]

Wing-forward Jim Parker (Archives New Zealand Reference: ACGO 8333 IA1 1349 15/11/17721)

His fellow wing forward in the Invincibles, Jim Parker, was a totally different type of wing forward again.

Parker was a real rover, very fast and fit, always on the ball. A very clean handler, and very good at joining up with his threequarters on attack.[12]

Because of the more positive aspect of their play, Porter and Parker were treated far better than Gallaher, but the combination of the wing forward and 2-3-2 scrum would linger for another seven years before the All Blacks were forced into line with the rest of the rugby world.

It would result in the most significant upheaval in the way New Zealand played rugby and it wasn't until the mid-1970s, apart from interim periods, that the All Blacks could claim to have recovered their scrummaging equilibrium.

NEXT WEEK: New Zealand assessments of Porter's men.

[1] H.F. Crowther-Smith, The Sketch, 3 December 1924

[2] V A S Beanland, Liverpool Post and Mercury, 1 December 1924

[3] F.J. Sellicks, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 6 December 1924

[4] Special Correspondent, Morning Post, 6 December 1924

[5] G.V. Portus, Sydney Mail, 23 July 1924

[6] E.E. Booth, New Zealand Times, 14 June 1924

[7] ibid

[8] ibid

[9] A.H. 'Arthur' Carman, New Zealand Sportsman, 15 June 1935

[10] ibid

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

The Welsh team, especially the front 5 are still not fit enough 100 years later !