The French games at the end of the Invincibles' [they could now be called that] tour are forgotten in the drama of the great Test against England. But given the rivalry that started to develop with France in the 1960s, the 1925 games have their place in New Zealand's DNA rugby strands.

In the Paris game against the Selection Française, played on a Sunday in front of 55,000, the French looked to attack, but the All Blacks' well-honed teamwork and constant backing up allowed them few chances.

Many of our tries were scored with several men outside the scorer waiting for a pass. We beat our opponents in all departments, and our attack was persistent, the ball travelling from one man to the other with great rapidity and certainty. Eight tries, all with the exception of one being from passing rushes, were scored before halftime, none of which were converted.[1]

The Times made similar comment.

Except during the opening five minutes of the game and for the first quarter of an hour of the second half, the Frenchmen were quite outclassed. At times, in fact, they appeared to be completely bewildered by the magnificent manner in which their opponents, who gave one of the best displays of their tour, backed each other up, made splendid and effective use of the return pass, and constantly changed the direction of their attacking movements.[2]

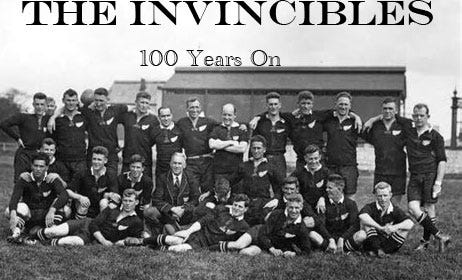

Winston Churchill had been in Paris to attend the Inter-Allied Commission dealing with peace treaties post-World War One and took the chance to watch the All Blacks in action. (NZ Rugby Museum)

Captain Cliff Porter astutely noted a rugby trait that would be significant in later years of the contact between the sides. He told Gordon C. Jones in an exclusive interview that the French, especially the Selection side in France, had been far superior to the British and Irish sides in the application of science.

The French footballers were not dismayed by the huge score piled up by the tourists and had been 'triers to the end'. They had shown that they could exploit unorthodox tactics, a point in which British teams generally had failed, and their system of penetration was effective if they could work up combination. There they had failed, however, for their positioning was not really good at times, and their passing was responsible for many failures. They had some fine men out, and the side was capable of being made a really tough proposition.[3]

And so say the sides led in the modern era by Graham Mourie, Jock Hobbs, Taine Randall, Richie McCaw, Sam Cane and Scott Barrett.

The victory was one of teamwork, plus individual cleverness, against mere individual cleverness. The French had ample pace, but they were not in the same class as a team. The passing and reverse transfers were a feature of the New Zealand play, and the unvarying height and well-judged speed of the transfers had a very great deal to do with the success of the movements. There were many instances when the ball was handled by as many as eight men, and backs and forwards combined in this type of attack with fine effect. It was hopeless for the French to combat offensives launched in this manner.

The had not the gift of anticipation developed to the same degree as their opponents, and repeatedly they were baffled by the dummy pass and by the cool side-stepping of their tackles.[4]

Halfback Clement Dupont, a member of France's 1924 Olympic Games silver medal-winning side, did score a try during the first-half dominance by the All Blacks. And, in the second half, flyhalf Yves du Manoir kicked ahead and followed up to get the bounce to score as the French dominated the third quarter before the All Blacks scored three more tries to end with a 37-8 win. The French side was down to 13 by the end of the game, with two of their players injured.

Scorers: Selection Francaise 8 (Clemont Dupont, Yves du Manoir tries; - Pelletey con) All Blacks 37 (Cliff Porter, Gus Hart 2, Cyril Brownlie 3, K.S. Svenson 2, Maurice Brownlie 2, Bert Cooke tries; George Nepia 2 con). HT: 3-24. Referee, W.J. Llewellyn, NZ touch judge, S.F. Wilson)

E.E. 'General' Booth said the Test match in Toulouse, played in front of a smaller crowd of 35,000 at the home of France's champion club, Stade Toulousain, was a revelation after the disappointments of the Paris game. But local punters were so enthused play was delayed 15-20 minutes after a traffic build-up near the ground. So many people were crammed inside the ground that the All Blacks struggled to get to their changing rooms.

Eventually, a fence we were fighting our way along collapsed, and the pressure was relieved just long enough for us to scramble through a back door which led into the basement of the grandstand.[5]

France's Test side showed better fitness and initiative, especially in the confidence with which they attacked and counterattacked. Their determination was evident to the All Blacks, and France enjoyed a more significant share of territory than the score suggested. But they lacked the polish to finish off their opportunities.

They displayed great energy in the open and packed solidly in the tight, with the result that we had to work hard all through the game. Both the French tries were scored by forwards, and were the direct outcome of purely vanguard offensives, which made almost 50 yards of ground on each occasion. We had had a 'let up' after our strenuous time in England, and consequently, our play lacked a certain amount of 'sting.'[6]

Booth said the score was closer than the final points difference suggested, as two of the All Blacks' tries resulted from forward passes, which had more than a little to do with referee Major Wilkin's inability to keep up with the speed of the All Blacks' passing rushes.

I have never seen a French team play with such confidence. They fully expected to be beaten but they intended to make New Zealand do its very best...This Toulouse game was not an exposition of very skilful play. The All Blacks, as in so many of their matches in England, won by their superior teamwork the most outstanding feature of which was their magnificent backing up.[7]

Porter had the satisfaction of opening the All Blacks' scoring when completing a breakout started by a Freddie Lucas intercept and a rush carried on by Jimmy Mill. France took the attack to the All Blacks' 25-yard area, but Maurice Brownlie's breakout saw Lucas, Bert Cooke and Steel combining for Steel to score after a long run to the line. Then, Cyril Brownlie passed to Cooke, who made a break that saw Lucas feed Karl Svenson in for another try. Loose forwards 'Son' White and Jock Richardson, each ran in tries from a distance to give the All Blacks a 17-0 halftime lead.

France scored consecutive tries in the same corner in the second half. Both came after fine rucking by the home side with flyhalf du Manoir giving good ball to his outsides, who did not always take full advantage of their chances. Booth's comments would ring true, given the mercurial play of later French sides.

Nearly all the French backs possess speed and certainly play in unorthodox fashion. They still lack a certain amount of theoretical knowledge, yet during this game their play was wonderfully correct. Thus during the whole course of the game they were only penalised three times.[8]

Porter felt the Test match, the only one in which he played on tour, had seen a lot of scrappy play and individualism from the French and while that suited the Toulouse crowd, the rugby was not of the same class as that in Paris.[9]

Bert Cooke recalled that du Manoir, a pilot in the French Air Force, was killed in an air crash three years after the Test match.

The All Blacks finished confidently, with Bill Irvine capitalising on Mark Nicholls' work to score, and then Cooke scored twice, his second try resulting from a Svenson cross-kick.

Booth believed the All Blacks were at their most cohesive in the France Test. Richardson and Maurice Brownlie were outstanding, and on the occasion when they and 'Son' White were left unmarked at lineouts, it was fatal as they took their chance to ensure tries were scored.

The game was quite up to International standard comparing more than favourably with the previous Internationals against Wales, Ireland and even England. It is possible that the New Zealanders actually played hard to win this game and showed better form than they did in the other internationals.[10]

It said much for the All Blacks' fitness that they finished the tour showing their best form. But Masters felt France showed they were a growing force.

Unlike many of the teams we met in England, the Frenchmen met attack with attack. They possessed plenty of speed and weight, and being enterprising, should, with the experience of a few seasons up against better teams, give their neighbours across the Channel a hard tussle for the Rugby supremacy of Europe.[11]

A little-known example of the popularity of the All Blacks in France was seen in Toulouse when the local club skipper approached the All Blacks and asked if three players could appear for Stade Toulouse in their next game. Alf West and Alan Robilliard duly played, but the opposing skipper became upset when West scored a try and couldn't respond to his comments in French, not helping the situation when he replied, 'Oui, oui, Monsieur'. West was sent from the field for not being a regular Toulouse player, only to be replaced by Jim Parker. Parker and Robilliard continued to play with their nationality undetected.[12]

Scorers: France 6 (Cassayet, Ribere tries) New Zealand 30 (Cliff Porter, Jack Steel, Karl Svenson, Andrew 'Son' White, Jock Richardson, Bill Irvine, Bert Cooke 2 tries; Mark Nicholls 3 con). HT: 0-17. Referee, Major H.E.B. Wilkins, NZ touch judge, Stan Dean.

NEXT ISSUE: Player Profile, George Nepia

[1] Read Masters, With the All Blacks in Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia 1924-25

[2] The Times, 17 January 1925

[3] G.C. Jones, Poverty Bay Herald from interview with Cliff Porter, 27 February 1925

[4] Jones, ibid, 26 February 1925

[5] Masters, ibid

[6] ibid

[7] E.E. 'General' Booth, NZ Truth, 7 March 1925

[8] ibid

[9] Jones, Poverty Bay Herald, ibid

[10] ibid

[11] Masters, ibid

[12] Jones, ibid