Innovation, the cornerstone of much the All Blacks have achieved and continue to achieve in rugby, helped the 1924-25 side overcome the severe disadvantage of playing 70 minutes of their tour-defining Test against England with 14 men.

The loss of loose forward Cyril Brownlie early in the game will be studied in the next issue of The Invincibles 100 Years On, but for those on the field at the time and on the back end of a ferocious 10 minutes of assault from England, an instant fix was needed.

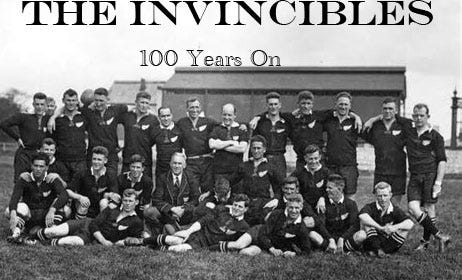

The fateful moment when Cyril Brownlie was ordered off Twickenham nine minutes into the crucial Test. (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19250226-47-01)

The side's combination, built up on the tour and refined for the last big game during a week spent at Deal, needed to adapt to the crisis.

The immediate choice was to eliminate their rover, Jim Parker, and bring him into the pack at the expense of an extra man in the backline.

That required halfback Jimmy Mill, five-eighths Neil McGregor and Mark Nicholls, and centre Bert Cooke, to assume much more of a defensive role to cover the speedy England backline without Parker's speed to assist. It also required the powerful remaining forwards to wear down their English opposites.

Yet, the All Blacks' response to the shock impressed.

It was natural enough that they should be rattled for a time, but they recovered themselves splendidly, and the forwards especially deserve high praise. The taller men were the more prominent, but all seven must have worked relentlessly.[1]

Ron Barr said the All Blacks' were the victims of farcicial scrum control.

…there were incidents of 'devilish' play, occasioned by the great issues, or terrible footwork, that had only one meaning; of 'scrapping' on the lineout; of handling in the loose, and of scrambling scrums, screwed yards beyond the position, but never reformed or brought back. The scrums, in most instances, were a farce, and on many occasions the methods of putting the ball in was nothing so reminiscent as of the so-called scrums in the League game I have seen in New Zealand. I have only witnessed once, on the tour of the All Blacks in Great Britain, a worse exhibition of scrum formation than that in the great international test at Twickenham on January 3, 1925. I hesitate to think that would have happened if any such methods had been attempted in New Zealand.[2]

What was surprising was that in the first 20 minutes, England had scrummed well, but for the remainder of the game, England's pack persistently packed, started to move before the ball was anywhere near and moved the scrum away from the mark only never to be brought back by the referee. On their feed, England's halfback put the ball at the feet of his nearest man, and he kicked the ball back to the halfback, who then ran around behind the scrum to get the backs moving. However, England's backs let the side down, in spite of the fact that individually, they had faster players than the All Blacks. They showed none of the initiative, flair or support that were the hallmarks of the All Blacks' game.

Neither Davies nor Corbett were distinctly impressive, and Hamilton-Wickes got few chances. Young played a bright game behind the scrum, and Kittermaster at flyhalf was a success; his run through a drawn defence down the field from the half way line was one of the thrills of the game and his try was the best of the day. Brough was safe at fullback, but his line kicking was short, and he certainly did not save his forwards. In contrast to Nepia's magnificent line kicking the English fullback was weak.[3]

Early on, Young fed Davies, who sold a dummy and broke the line with only Nepia to beat with Hamilton-Wickes on his left and Corbett and Gibbs on his right. Fortunately for the All Blacks, he chose to pass to Corbett, the only man Nepia could have tackled, and he made no mistake. Gibbs went close, having Cooke push him out in the corner.

Barr said that the All Blacks' tackling was tenacious. The forwards, once they settled, were great.

There was no 'beg your pardon' in this game – the issue was too great. Maurice Brownlie stood out as the great forward on the ground, and Jock Richardson was not far behind, with the whole pack playing for the prestige of New Zealand. It was a thrilling game and the pace was superb, the brilliancy of the speedy backs in straight, determined, dashing down-field running was a delight to the 60,000 spectators who cheered to the echo these thrilling incidents.[4]

England missed another chance when a Hamilton-Wickes crosskick was spoiled by Davies throwing a bad pass. The All Blacks put their first passing movement together, and a Nicholls dropped goal attempt just missed. But that set New Zealand into a more consistent series of attacks. Richardson and White tried to get through before M. Brownlie emerged to throw a pass to Cooke. Cooke took it before Nicholls dodged his marker and passed to Svenson, who crossed out wide. Nicholls' conversion grazed the posts and it was 3-3 after 30 minutes.

A scrum was won when Brough was caught by Cooke. From it, Steel got the ball and ran hard down the sideline, bumping off two tackle attempts before diving to score in the corner.

New Zealand were now clearly on top and showing much improved form. The forwards were getting the ball from the scrums and M. Brownlie, Donald and Richardson were coming away with great rushes and having the best of the play. With four minutes to halftime Nicholls added three more points for his side, Voyce being caught paying too much attention to Mill. A penalty was awarded to New Zealand and Nicholls made no mistake, kicking a neat goal.[5]

England started with the wind in the second half, which required McGregor and Nicholls to make good defensive plays. Play continued to range up and down the field before Steel was pushed out near the corner.

We were not to be denied, however, for the next minute saw M. Brownlie making one of his terrific runs, smashing through the opposition and fending off several tacklers to score a most brilliant try. Nicholls kicked a magnificent goal from near the touch line – 14-3.

Keeping up the pressure our forwards were too good for the English pack, who were at this stage tiring badly, and a rush from halfway saw Richardson, Irvine and White very prominent, the ball going to Svenson, who cut in, and finally Parker raced over inches from the flag. Nicholls failed – 17-3. With such a lead the game looked all over – only twelve minutes to go.[6]

But England rallied, Gibbs fending off Steel and making a superb sideline break at speed. Nearing Nepia, he punted ahead, but Son White was covering to claim the ball.

England threw everything at moving the ball to their wings to utilise their superior speed over Steel and Svenson. Gibbs made another break, beating several tackle attempts to again punt over Nepia only to see Mill win the 25 touchdown.

The All Blacks put Parker on Gibbs' wing. But from an England scrum, the All Blacks backs were ruled off-side, with Corbett landing a dropped goal.

Mill and McGregor combined to take play to England's line, where Mill nearly scored. From a five-yard scrum, England secured the ball. Kittermaster ran across his posts and fed Davies, who passed to Hamilton-Wickes.

Like a dart he flew down the touch line, beating off all efforts to cut him off, and cleverly swerved infield. On he went to well inside the New Zealand half, and then deftly, at the right moment, having drawn the fullback, he passed to Kittermaster, who out-distanced the field to score the best try of the day under the posts.[7]

Nicholls rated Nepia as the player of the day for his best display of the tour. He kicked with more length and better direction than at any tour stage. He managed to wear down the English pack to make a significant contribution to the win.

Nicholls wasn't alone in that view. One local critic said,

Outside the scrummage G. Nepia was the man of the day. His last display in England was his best, for his kicking was much more consistent in length and direction than it sometimes is. As usual, his catching and fielding were faultless.[8]

Nicholls also praised the forwards.

M Brownlie was easily the best forward on the ground, and I do not want to see a better one. Richardson and White were more prominent than the others – Masters, Donald, Irvine and Parker – played together as one man, going right through the English pack at times. Most of the attacks were started by the forwards, and they held the English eight, gradually wearing them down…Wakefield was the best of the English pack, playing a great game. He was ably backed up by Cove-Smith, Edwards and Conway.[9]

TPW in The Observer was critical of England's defence. He said Svenson's try would not have been scored had Bert Cooke, who threw the long pass to put Svenson clear, been appropriately tackled. He was hit high and lifted in the air, but his arms were free to throw the key pass. Steel also beat three defenders, and while some claimed he was out, the bad tackling was as bad as not playing to the whistle.

Many times in the game, the New Zealand forwards were allowed to break away with the ball and start passing, and when they were tackled, it was sufficiently gently to enable them to turn round and look for another man to pass to. I know they are very big and strong men, those All Black forwards, but surely that is all the more reason to tackle lower than ever. It never is much good going for a man round the hips, about the toughest part of a Rugger player's body, and the most vulnerable spot is at the knees. The first New Zealand try amazed me very much, not because of the score, but in consequence of the supreme ease with which it was done. The English backs allowed themselves to get hopelessly out of position. Two men both went for Cooke – and went high – and Svenson simply walked over.[10]

Long-time English writer Howard Marshall said the All Blacks were superior in combination and physique with playing qualities he would never detract. They had secured a fine record, avoided staleness by keeping fit in the most trying climatic conditions.

They proved that strength, speed, and fitness are the three chief factors in a team's success, for from these factors follow the virtues of backing-up and combination.[11]

Marshall recounted that when he began to play rugby he was told, 'A good forward should aim at being never more than a yard from the ball.' That was what the All Blacks' forwards aimed at, and they achieved it because they had the speed, and they had the fitness to maintain speed. That meant that when they got the ball they had the strength to do something with it.

If they were not all within a yard of the ball, one of them always was, and they were all within a yard of one another.[12]

Scorers: England 11 (R. Cove-Smith, H. Kittermaster tries; G.S. Conway con; L.J. Corbett penalty goal) New Zealand 17 (Snowy Svenson, Maurice Brownlie, Jack Steel, Jim Parker tries; Mark Nicholls con, pen). HT: 3-9. Referee, A.E. Freethy, NZ touch judge, Lou. Simpson.

NEXT ISSUE: Anatomy of a controversy

[1] F.S. Sellicks, The Cricketer, January 1925

[2] R.A. Barr, Southland Times, 21 February 1925

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] H.E. 'Ginger' Nicholls, NZ Free Lance, 25 February 1925

[6] ibid

[7] ibid

[8] F.S. Sellicks, ibid

[9] Nicholls, ibid

[10] T.P.W., The Observer, 11 January 1925

[11] H.P. Marshall, All Sports Weekly, 17 January 1925

[12] ibid

My rugby master at school always screamed at us( i played No 8) to always be within a yard of the ball !!!