England, unbeaten on Twickenham since losing to South Africa in 1913, loomed as the last chance to puncture the All Blacks' balloon on their tour.

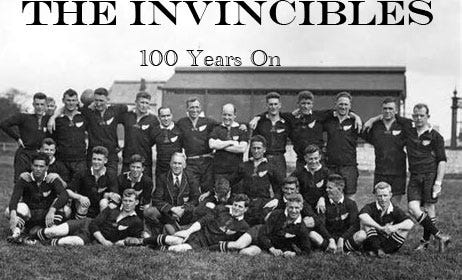

From the tour's outset, the general feeling was that it seemed impossible for Cliff Porter's men to do any better than Dave Gallaher's side of 1905. But they arrived at Twickenham with 27 consecutive victories on their tour against the best England, Ireland and Wales could throw at them.

Few were prepared to back an England win, although hope was the constant friend of supporters.

Touch Judge in the Sporting Life and Sportsman said a friend's comment that England would win was farcical.

Not a dozen out of the 60,000 that are expected to be present honestly believe this to be possible.[1]

He said it was The Rugby Union that would be responsible for England's loss because they organised the game without England having a chance to play together.

The New Zealand team, as invariably is the case with a touring side, are a happy family who, in the course of twenty-seven encounters, have become a perfect machine both in attack and defence.

They are meeting a side that not once has played together and who possibly will be concerned for a long, long time in attempting to discover that 'the other fellow' is doing or desires to to.[2]

Another critic took The Rugby Union to task for playing only one trial game ahead of the Test, compared to three in the years previous. [Another game, North v South, was played but did not include university players, while fullback Henry Franklin, a county cricketer for Essex who had played so well for London Counties, was not included. It was regarded as inadequate preparation for the Test] It was a season that demanded the England team be brought together as soon as possible.

The single trial, England v. The Rest at Twickenham, on December 20, was a disastrous failure, and in the end did far more harm than good. The most tragic of its results was the dropping of E. Myers, whose absence on January 3 in all probability cost England the match.[3]

A.J. Harrop believed the confidence English critics, especially those in the tabloid category, felt after seeing the All Blacks struggle to a win in their first tour game became irritating the longer the tour went. Their early prophecies slipped further and further away. He said F.J. Sellicks's weekly comments in the Morning Post and invented interviews in The People were the classic examples of what the All Blacks had to endure in the press.

In England it appears to be the practice for everybody connected with any game, from the man who marks the lines and sweeps the ground down to the referee to give opinions for publication. The All Blacks did not indulge in this, and their opinions were imagined for them.[4]

The comments, which have echoed throughout All Blacks history, only fired the All Blacks' determination.

The Athletic News said:

No one would have minded England being beaten: indeed the defeat might have been welcomed had it been brought about by brilliant play, collectively or individually. But that consolation was denied us-the little brilliance there was was swallowed up in an enormity of mistakes.

That was the disquietening factor. The 'All Blacks' have shown us in match after match that they do not worry if the other side get the ball from eight out of every ten scrimmages. Their defence is sound enough to bottle up most attacks, even if they are carried out with precision, while the slightest lapse from rectitude is seized up and usually turned to very considerable advantage.[5]

Mercian said the team was selected on the wrong basis – safety.

Analyse the backs, and the impression one gets is that the object has been to attain the highest possible degree of safety. There is none of the gambling element about it...It is a dry ginger team without the sparkle of champagne...There is, unfortunately, a big gap between the English team of last season and the English team of this and I, for one, think that the New Zealanders, with their pace, weight, combination, and skill will win with some ease.[6]

Four new caps were included in England's squad. Fullback 'Pup' Raymond, the Australian, dropped out of the team before the Test. The others were flyhalf Harold Kittermaster, prop Ron Hillard from Oxford University, and Cumberland fullback and double England international in rugby and soccer, Jim Brough.

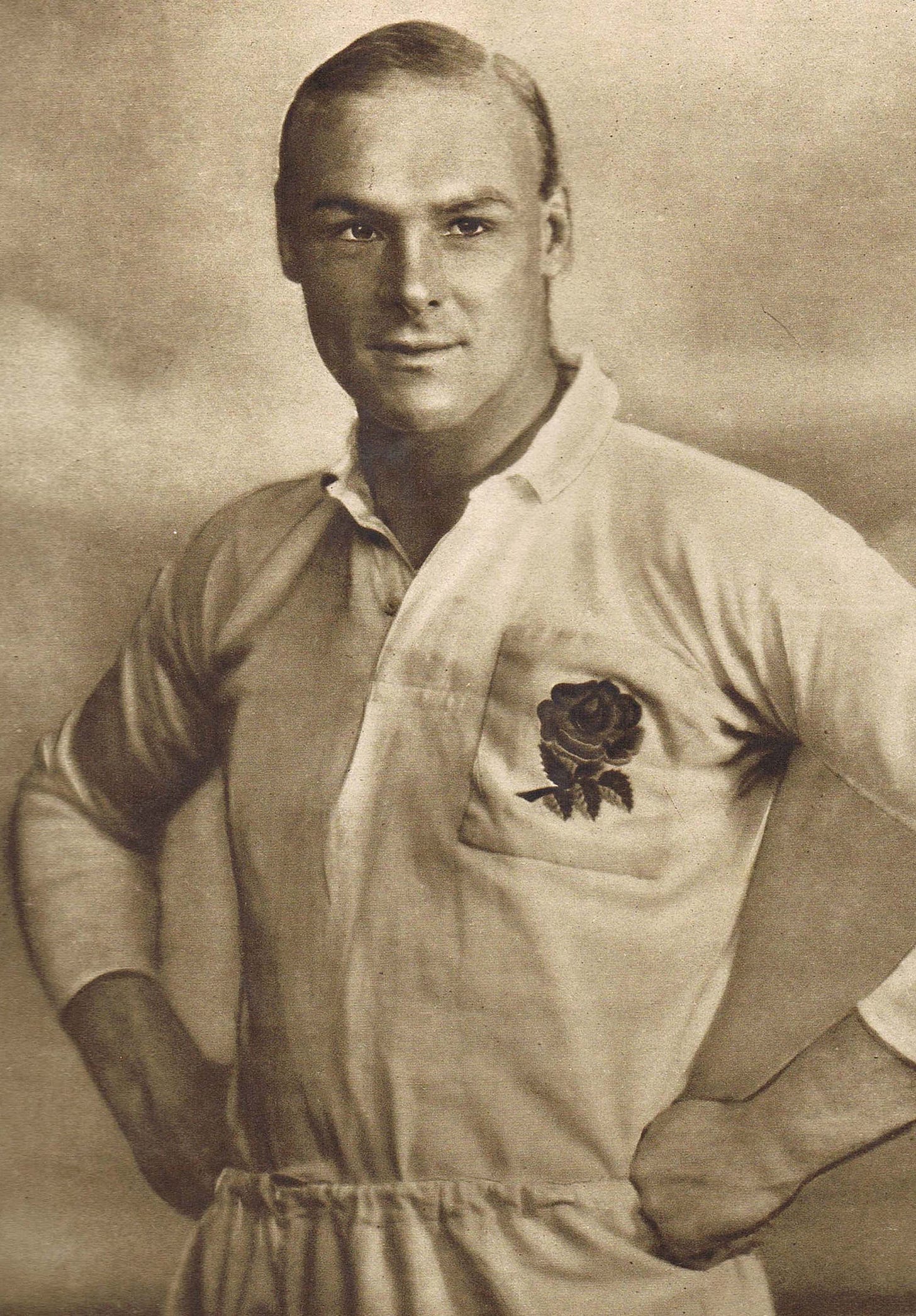

England captain Wavell Wakefield

Eight of the side returned from the 1923-24 season. Wing Richard Hamilton-Wickes played for London Counties and Hampshire against the All Blacks, and centre Len Corbett played against them for Gloucestershire. Halfback Arthur Young had toured South Africa with the British & Irish Lions and played for Cambridge University against the All Blacks. Captain and lock Wavell Wakefield played for Leicester and London Counties against the tourists, while lock Ron Cove-Smith, another Lions tourist, also appeared for London Counties. Lock Geoff Conway captained Lancashire against the New Zealanders and was regarded as the most complete of England's forwards. Flanker Arthur Blakiston was also a Lions tourist and captain, while prop Reg Edwards led Newport. Returning from earlier seasons were inside centre Vivian Davies from Harlequins, Leicester flanker Leo Price, who had the feat of playing rugby and hockey for England on consecutive Saturdays, and hooker Sam Tucker from Gloucestershire.

Hopes were high that England could prevent an unbeaten tour, but those with more of an understanding of the game were more realistic. The Daily News quoted a member of The Rugby Union's response when his friend criticised England's side, 'My dear man, if we picked our best thirty instead of fifteen, we couldn't beat them.' The paper added,

The All Blacks are the greatest Rugby side on earth. There is no element of mystery in their invincible prowess. They have not discovered some radio-active secret for use as athletes. They merely combine the qualities of a beautifully-running machine with quick, human resourcefulness.

They are big, strong and speedy, and so physically fit and in such perfect training that they wear out even their most dangerous opponents in the first half-hour and beat them in the last 40 minutes. Their giant forwards play like three-quarters, and their three-quarters have the thrusting power of armour piercing shells. Nothing in British or French football today can compete with their comsummate skill and demoniac energy. Only a miracle will save England from defeat on January 3.[7]

As for New Zealand's team, it was clear in the last few games, especially those wins over Combined Services and London Counties a week before the Test, that the team was well settled. The only question was whether captain Cliff Porter had done enough to warrant inclusion for his first Test of the tour.

It was understandable that Porter would want to play in THE game of the tour, but it wasn't to be. He explained what happened at the key selection meeting.

I had wanted Jim Parker, who was one of the fastest men we had and who was playing magnificent football, to go on the wing in place of Jack Steel, whose form had slipped badly. I reckoned England, who wanted to break our run of successes, would play rugged football, and that's where I would have been in my element, giving our backs the chance to feed Parker, an unstoppable winger on the day. But Jock Richardson didn't see it that way, and rather than cause a rumpus in an entirely happy team, I conceded the point.[8]

Richardson told his version of the selection meeting in which he and manager Stan Dean felt Parker was in better form.

Porter thought he could play against England, but it wouldn't have been fair on Parker. He didn't deserve to be dropped. In the end, I said Parker deserved his place.

Dean and I said he could play against France to get an international cap, but on that tour, Parker was the better player. He was so fast. He was the sprint champion of New Zealand and was the fastest man in the team, faster even than our best winger, Steel. He had football knowledge and sense. If Parker and Porter had been at the top of their game, it would have been a real selectors' headache.

I could understand Cliff's attitude at the end. It must have been difficult for him. To his credit, we kept the whole business private. It was a 2:1 vote against him, and once it was taken, there wasn't a word spoken of it to the rest of the team. It's no good fostering dissension.[9]

Of the New Zealand media on tour, H.E. 'Ginger' Nicholls felt the All Blacks side named could not have been better. Porter must have found disconcerting to stand down but he showed his sportsmanship in accepting the decision.

New Zealand should be proud to think they have had such a good man at the head of affairs for the tour.[10]

NEXT ISSUE: England's chance

[1] Touch Judge, Sporting Life and Sportsman, 3 January 1925

[2] ibid

[3] F.S. Sellicks, The Cricketer, January 1925

[4] AJ Harrop, The Press, 28 February 1925

[5] Mercian, Athletic News, 22 December 1924

[6] Mercian, ibid, 29 December 1924

[7] ibid

[8] Cliff Porter, interviewed by W.F. 'Wally' Ingram, Legends In Their Lifetime, A.H. & A.W. Reed, Wellington, 1962

[9] ibid

[10] H.E. 'Ginger' Nicholls, NZ Free Lance, 25 February 1925