Just how good was Maurice Brownlie?

Perhaps his 1924-25 All Blacks teammate, second five-eighths/centre Bert Cooke, summed it up best.

Upon hearing that Brownlie wouldn't play for the North Island against the South in the annual inter-island game in 1926, Cooke said, "I don't think I'll play. There's half our forwards gone."

The great England lock and leader Wavell Wakefield was in South Africa in 1949 and saw the Test series between the All Blacks and South Africa. He felt England could never compete with those two sides until they could produce forwards of comparable strength and physique, with speed, physical fibre, and the rugby intelligence of men like Brownlie.

Brownlie was as accomplished a forward as one could wish to see. I put him down as the finest I played against in my 12 years of international football. He was tough physically – a tremendously difficult man to pull down whether one went high or low because he had the strength of an elephant.[1]

He also added,

He was the complete forward, always on the ball.[2]

In an unattributed comment, TP McLean quoted Wakefield describing Brownlie's try in the final Test against England when New Zealand was reduced to 14 men due to his brother Cyril's sending-off.

The ball had fallen loose between J.C. Gibbs and R. Cove-Smith when Brownlie came through very fast and snapped it up. I had slightly overrun it, and as I turned, I was directly behind him. I could see him going straight down the touchline, though it seemed impossible for him to score. Somehow, he went on, giving me the impression of a moving tree trunk, so solid did he appear to be, and so little effect did various attempted tackles have upon him. He crashed through without swerving to the right or left and went over the line for one of the most surprising tries I have ever seen.[3]

As with many of the 1924-25 All Blacks who impressed, they were compared to players who toured with the Original All Blacks in 1905-06. For Brownlie, it was a case of whether he was better than Charlie Seeling.

One correspondent to the North Canterbury Gazette, 'The Pen', felt Brownlie proved himself the better man due to the better quality of forwards his side faced.

Brownlie had physical advantages over his great rival. Seeling, when he left New Zealand with the original All Blacks, weighed 13.5st, while Brownlie went 14.8st. In the matter of speed, there was probably little between the two men, while the tackling of both was devastating and here, Seeling was probably the more certain. Brownlie's handling was always exceedingly good, and he undoubtedly held an advantage in this respect, which made him more effective in the lineout.

Both had a tigerish intensity, which made them extremely unpleasant to face at times. Brownlie could play a fine game among the backs and, in his earlier days, was an exceedingly powerful place-kick. Both men could punt with power and precision, but Brownlie was the harder man to stop when underway.[4]

'The Pen' believed Brownlie also had it over Seeling in education.

No one was long in Brownlie's company, without discovering that he was an outstanding personality as well as a great footballer. And in rugby football, as it is played today, brains count.[5]

Comparisons with Colin Meads were made so often during Meads' career that Brownlie came to be regarded by some as a lock. But he was always a loose forward, packing on the side of the middle row of a 2-3-2 scrum. His stature would compare with the modern blindside flankers in the mould of Jerome Kaino, Jerry Collins or Alan Whetton of more recent times.

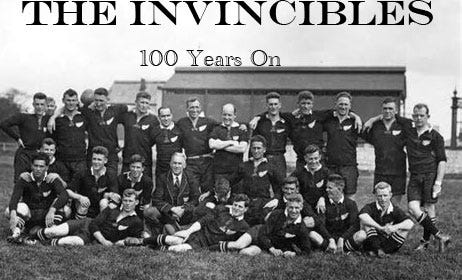

Arthur Carman said Brownlie was invariably one of the best-performing forwards in the 24 games he played on the 1924-25 tour.

Morrie is so effective in securing possession of the ball for his side, from the lineout or the loose, that he was invariably one of the hardest-working and most conscientious forwards in the team. He took the tour very seriously and was so well trained that he several times was in danger of going 'stale'.

I would not try and detail all the excellent games he played, but there is no doubt that his display at Twickenham in the January 3 international [against England] was the best. He displayed almost superhuman strength when, with several opponents clinging to him, he absolutely hurled himself across the line. One often wonders how Morrie keeps going as he does, as he uses far more strength than most players. He seems to have acquired the ability to apply every ounce of strength he possesses.

Critics often state that his fault is that of hanging on to the ball too long, but seldom does his side lose by it, and in any case, he gets the ball twice as much as any player and is entitled to vary his play.[6]

Carman added that the British newspapers had constantly referred to Brownlie as the best forward in the world, and he agreed that no forward on the tour got the better of him. Having seen two British and Irish Lions Tests in South Africa en route to Britain, he believed Brownlie was the best.

Brownlie's father, James, sowed the kernel for Maurice and Cyril, a year older of the two, of making the All Blacks. After their older brother Laurence was selected to play for New Zealand in the ill-fated 1921 game with New South Wales in Christchurch, James said to the pair, 'If Laurence can do it, you two can.'

They served in Egypt with the New Zealand Mounted Brigade after joining up at 18 and 19, respectively, to fight in the First World War. It was there they first made their names in rugby, playing along with 1924-25 teammates Jock Richardson and Jim Parker for the Moascar Cup.

Returning to New Zealand and working on the family's Puketitiri sheep farm, they played their rugby for Hastings. Morrie Brownlie famously contested and lost the heavyweight final of the 1920 New Zealand amateur boxing championships against Brian McCleary, a future 1924-25 tourist. Once some rough edges were knocked off the Brownlie brothers' rugby, they started to make their presence felt, and Maurice was first selected for Hawke's Bay in 1921. That was the year Laurence was selected for the North Island and won an All Blacks jersey, only to suffer a knee injury that ended his career.

Maurice's stature was appreciated quickly and in that first season, he captained Hawke's Bay-East Coast against the touring Springboks, with future world heavyweight boxing contender Tom Heeney in the side. In 1922, his performance for the North Island saw him named in Moke Belliss' All Blacks side to Australia. While he was touring, Hawke's Bay lost the Ranfurly Shield to Wellington. But, in 1923, Brownlie was appointed the Bay captain, and his influence was measured by the side's regaining the Shield and amassing an outstanding record of success.

As the Auckland Sun noted,

Hard-case footballers became unexpectedly docile when Brownlie was captain.[7]

So impressive was his command of men and his popularity among the rugby faithful that politicians wanted a slice of him. He was sought to stand as a candidate for Napier in the 1925 Parliamentary election.

The Sun noted that socially, he was a man of substance and a rugby player who, at times, was a little short of 'super-human'. And while as a captain, he might be too austere to be generally popular, he was a sincere leader.

Six feet in height, and fourteen stone in weight, and a man of prodigious strength, he is perhaps the finest physical specimen that has ever represented New Zealand.[8]

Brownlie thrived on the action, and while some felt he might have passed the ball closer to the opposition goal line, he was always a powerful force, on or off the ball. He didn't like sitting on the sidelines and when rested for the ninth game, the 18-5 win over Cheshire, he told Mark Nicholls of his frustration.

Speaking to Morrie Brownlie after the match he told me that this was the last match he wanted to watch, inferring, of course, that the form was so bad that he wanted to play in every other match.[9]

Of the next 24 games the side played, Brownlie appeared in 18. It is a measure of the times that he played only eight Test matches in his career and 61 games for New Zealand, a record that stood until beaten by Kevin Skinner in the 1950s. And for all the greatness associated with his involvement in the great Hawke's Bay era of the 1920s, he made only 43 appearances for the province.

Brownlie felt the Oxford game was the most difficult on the tour. The final score could not reflect the closeness of the game.

Oxford was the most dangerous from first to last, and they had a strong back division.[10]

Brownlie created some interest at the same function when he stated that the All Black name should be dropped because many people, especially in Canada, had misunderstood the term 'All Black'. Locals expected the players to be black-skinned. He felt a better title should be found for the side.

He also felt refereeing in England was affected by the lack of a referees' association. Without a governing body, the laws could not be stabilised, and referees were left to their own interpretations. He also found that the French, while on a par with England, were more in line with New Zealand's attitudes towards the game in adopting laws that benefitted the game.

And, in a portent of a possible future dispute with Mark Nicholls, who decried the 2-3-2 scrum, Brownlie said it could not be improved upon.

If the ball was properly put into the scrum, the 2-3-2 formation beat the 3-2-3 formation every time.[11]

His greatest asset was his physical acumen. The All Blacks lock on the 1928 tour of South Africa, Geoff Alley, a future director of New Zealand's National Library, described Brownlie's qualities.

I can think of his contemporaries who were faster – Cyril, his brother, and Ian Harvey could both give him yards in a hundred and beat him. There were forwards who, on their day, were better lineout forwards, better-scrummaging forwards, or even better loose forwards. But, what made Maurice a king among the forwards of his day was that he was capable of producing really superb form in any of the departments of forward play, yes, even in tight play – when the occasion demanded it, and he had that steely quality of mind that enabled him to reach down into the last corners of his great physical resources for the extra effort to cope with a critical situation.[12]

Alley said he had long remembered the North-South match on a wintry day in Invercargill in 1925.

I have never forgotten seeing him carve his way through half a team using that characteristic jabbing fend and with his rather individual high-kneed running action. No one seeing Brownlie in his best form as a forward would forget him. Seeing him in the showers without clothes was to realise again what the Greeks succeeded in doing in making the human form the subject of their sculpture.[13]

Alley said the longevity of Brownlie's career, especially considering his First World War service, was remarkable given the strains and stress he faced. However, 'it says a lot for his superb physique that he could go through this period without faltering.' That was more the case because of the Ranfurly Shield era he played through.

Alley said Brownlie's role in the second and fourth Tests in South Africa summed him up. In the second Test, little was seen of him in the loose or any other forward.

It was the complete answer to those who said scornfully at the beginning of the tour that 'these chaps will be beaten because they won't scrummage.' As the first scrum went down and met the Springbok pack, the crowd was amazed to see the transformation. The New Zealand pack pushed South Africa off the ball – and continued to hold the mastery. So here was another Brownlie, a tight forward grappling his lock with arms of steel.[14]

And in the fourth Test, which Alley said was one of his greatest,

As a captain, his role was that of leader, and he preferred to lead from the front. He was not, and never tried to be, a tactician. On that day in the welcome moisture of Cape Town, with a greasy turf to play on, it was the Brownlie of 1924 and 1925 that we saw, and the result, a 13-5 win, was a personal triumph for him as well as for his side.[15]

Given the significance of that occasion in 1928 and the extra pressure involved in having a sibling removed from the field against England in 1925, they are probably the appropriate answers to the question asked at the top of this profile, 'How good was he?'

Maurice Brownlie was the player of a generation and thoroughly worthy of the stature he enjoys.

[1] Wavell Wakefield, The Press, 9 October 1963

[2] Wakefield, Rugby World, December 1975

[3] Wavell Wakefield, quoted, unsourced, by TP McLean, New Zealand Rugby Legends, MOA Publications, Auckland, 1987, p152

[4] The Pen, North Canterbury Gazette, 13 April 1933

[5] ibid

[6] Arthur Carman, Daily Telegraph [Napier], 29 July 1927

[7] Maurice Brownlie, A Prince of Forwards, The Sun (Auckland), 30 March 1928.

[8] ibid

[9] Mark Nicholls, Weekly News, 9 October 1935

[10] Maurice Brownlie, response to written questions when welcomed home in 1925 by his Hastings Football Club, Hawke's Bay Tribune, 26 March 1925

[11] Brownlie ibid

[12] G.T. Alley, Brownlie Obituary, New Zealand Broadcasting Services, 27 January 1957

[13] Alley ibid

[14] ibid

[15] ibid