You won't find Andrew ' Son' White's name mentioned among the heroes of the Invincibles tour too often, yet his story of achievement is one of the most compelling.

The Southlander, from Invercargill's Waikiwi club, was a survivor of some of the most horrific war campaigns to which New Zealanders have been exposed – Gallipoli, the Somme, Messines and Passchendaele—all names writ honourably in New Zealand military history.

White was 20 and a farm labourer since the age of 13 following his father's death when war broke out, and he had not had a chance to make his mark in Invercargill club rugby. During the war, his opportunities to play were limited as regimental and other Army selections were based on players who had established playing records before the war.

He was part of the Otago Mounted Rifles, decimated in the Gallipoli campaign, and confined to hospital for three months before he was made a driver of horses for the New Zealand Field Artillery. A victim of field punishment after a court martial when leaving his French billet, getting drunk and assaulting a military policeman, he was given four weeks' punishment, including being tied to a post during the day.

But there were no military parades, no significant honours when White returned. He came home shell-shocked in 1918, officially described as 'greatly infirmed' with hearing and breathing issues, a tremor in his hands, a nervous disposition and a high pulse rate regarded as dangerous. Nowadays, there is a much greater understanding of post-conflict trauma, but in his time, people far removed from the action could be harsh in their judgments.

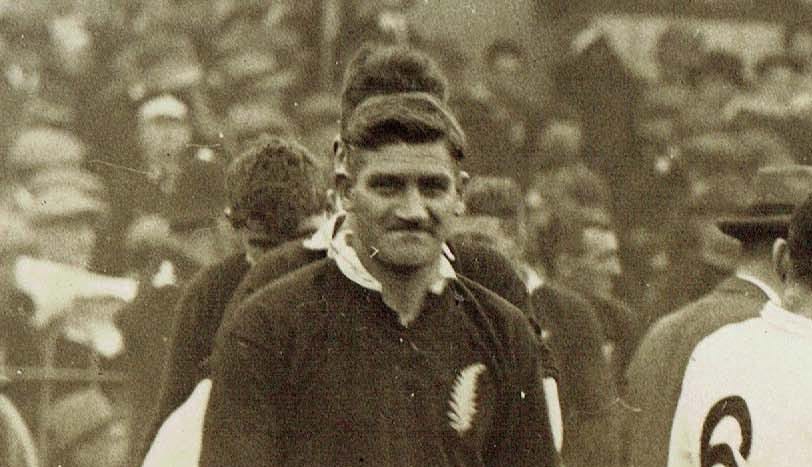

‘Son’ White honoured with captaincy after team vote (NZ Rugby Museum)

For many trauma victims, time would have been scheduled in institutional care. But not for White. Rugby would prove his aid to some form of normality.

What must have gone through his mind when Britain's military leaders, many of them from the High Command, turned out for a dinner for the All Blacks?

By the time rugby resumed in 1919, he was 25 and working as a storeman. But he worked his way back to fitness and was selected for his first game for Southland at the end of the season.

However, 1920 was much more productive for him as he shared in the glory when Southland won the Ranfurly Shield from Wellington. The Northerners took the trophy on tour, and the Southlanders were the first South Island team to win it.

White played for Southland against the touring 1921 Springboks and, two weeks later, was part of the first Shield defence when Otago was beaten. These games followed his appearance in the North-South game, where he scored a try in the South's 13-28 loss. He also played in the final trial to select the All Blacks to meet South Africa in the first Test, won by New Zealand 13-5. However, while the All Blacks coach Billy Stead thought White was the best forward on the field, the selectors, of whom Stead was not one, decided otherwise, and he was dropped. He appeared in an All Blacks B team that suffered a shock 0-17 loss to New South Wales later in the season but did well enough to be one of the first chosen for the 1922 All Blacks tour to Australia. That followed a 9-8 win for the South in the inter-island game.

While not selected for the South Island in 1923, he was among those called in for the third 'Test' against New South Wales in Wellington, a game won 38-11 and of significant importance for those looking to tour Britain, Ireland and France in 1924.

Through the rigorous trial process ahead of the tour, White played well enough to be among the first 16 selected.

NZ Truth said of his choice:

White is perhaps the most honest forward playing in New Zealand today. He covered himself with glory at Wellington in the inter-island game. As an exponent of dribbling he has no superior in New Zealand, and the point about his work in this direction is that in most of his essays he comes through the pack with the ball at toe – no waiting in the loose for him.[1]

On the warm-up tour to Australia, White, 30, he played all four games, a prelude to his appearing in 21 of the 30 games in England, Wales and Ireland, not bad for the second-oldest man in the team.

Arthur Carman said he never saw White play a bad game and rated him one of the two best men in the All Blacks pack.

His experience, well-applied weight, expertness as a dribbler, and the fact that he never shirked the tight work, rather did he revel in it, more than counterbalanced disadvantages of weight and height – which disadvantages are, as a matter of fact, forgotten when thinking of 'Son' White. He was also a good player in the loose, and to this day I can see his dribbling of the ball down a rain-soaked, muddy ground at Cambridge, continually turning defence into attack when handling was futile, and repaying the Cambridge forwards in kind.[2]

White was consistently good and produced his best form towards the end of the tour, and by popular vote, he was awarded the captaincy against Hampshire when Cliff Porter and Jock Richardson did not play.

Reflecting on the tour, White recalled the close run against Newport early on.

The Newport match looked all up with us with five minutes to go. They were playing a hard, dirty game, and our boys were frightened to give anything back, on account of the crowd. I think it put us off our game, as we were playing rotten football.

Their first try was a good one. They were five points up at half-time. Their second try was not a try, but it made them 10-8. Five minutes to go, and they were two points in the lead. Cliffe [sic-Porter] said to us all: 'You've got to win.' That was really the only time our boys went for it, and Svenson scored with two minutes to spare. The try was converted.[3]

Like all the forwards in the side, he was frustrated by the way referees treated the scrum, especially those referees in the south of England. He felt the best referees were in the north, and in Wales.

The scrums have been awful, and the chief fault has been the side-row men breaking away too fast, and not putting their weight in. We have not been getting much ball from the scrums, but you can't blame our hookers, as they have not been getting the weight, and the referees have not been giving them a very fair go. In the match yesterday, we pushed them all over the paddock, but the referee would not let our men hook with the inside foot. Donald and Irvine were hooking. The ball goes in Donald's side. On his rulings yesterday, Donald could not lift a foot. If he did he was penalised.[4]

Ahead of the Ireland Test he was confident in the All Blacks' prospects.

There is a lot of interest being taken in it, but if the team play to form I am not worrying. We have a team talk about every match, and tear each other to pieces, and I think it is doing a lot of good. There are a few who won't take much notice, but I think it will do a lot of good before we finish. I like Porter as a captain and he is very popular.[5]

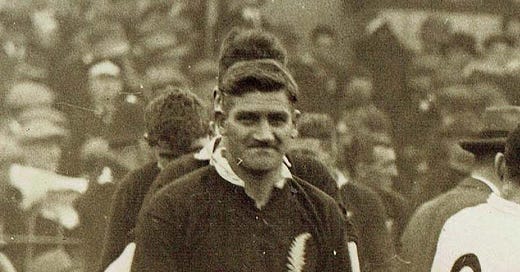

‘Son’ White on the burst with ball in hand (NZ Rugby Museum)

However, by the end of the tour the strain was starting to tell on many of the players and the relief at beating England was obvious.

Those who have never played through a long tour cannot imagine the great mental strain imposed upon members of a team. As our unbeaten record grew it was our pride as well as our bugbear. Those selected to play would often be unable to sleep the night before a match, wondering how they were going to get on. This was particularly noticeable in the final stages, and you cannot imagine the relief we all felt when we left the field after beating England. The tension was relaxed, and we were able to sit back and enjoy ourselves.[6]

White's innate rugby understanding has not been readily recognised in all the post-tour literature published across the years, but he revealed an understanding that spoke volumes for his rugby intelligence and added to the tour's legacy. His thoughts, buried in old newspapers for so long, are presented here in full.

Some doubt has been expressed about the relations existing among us but I can assure you that I do not think you would get another 29 players to make such a happy family. That was one of the secrets of our success. Every player was out for the success of the team, and no personalities were ever indulged in. We all stuck to training, and, by judicious methods, staleness was avoided and members were able to take the field for the various matches in the pink of condition. A lot of criticism of the team has been unfounded, and many good footballers under-rated the team at the conclusion of the Sydney tour. The Sydney matches were hardly a fair indication of what the team would develop into as members were not too keen about exerting themselves on the hard Sydney grounds.

The English referees are much slower than those in New Zealand, and their rulings were often difficult for the team to follow. They would often pull up the play where we could see no breach of the rules. Often [Bert] Cooke came through so fast that they were unable to understand how he got through, and they would penalise him for an infringement, being satisfied in their own minds that he must have committed one somewhere in his lightening [sic] dash for the open. Of course, we met a few good referees, but the majority of them were too slow to keep up with our style of play.

Our hardest games were against the Welsh teams, and we were not sorry to get out of that little country with our unbeaten record intact. The English play hard games, the Irish a little more strenuous, but the Welshmen put every ounce they possess into their play and never let up.

With the strain of travelling, and injured members, we were hard pushed in some of the Welsh matches, but now we can look back upon hard games cleanly won and recall various precarious moments in them when we were up against it.

It was always the aim of the team to make the play open and the forwards were soon almost as adept as the backs in picking up and giving passes. It was the backing up of the forwards and backs in attacking movements which won us many matches, but one important feature was never forgotten and that was 'run straight'. Straight running by all the team gained us much ground, while our opponents often lost ground, and tries, by forgetting this essential point in attack.

Our combination in defence was just as good as in attack, and all were doing their best whenever danger threatened our line. The style of play adopted by the British teams tended to slow up the game, and we were all the time striving to get the ball into the open. On dry grounds we were more successful, but on heavy grounds our task was more difficult.

Although we were successful in defeating every team we met, it does not mean that a British side can be treated with indifference. Many of the teams we met were combined sides, players being brought from a great distance to play for a county or nation. A British side, once it gets into training and obtains a little combination, will be very hard to beat, and will give our best sides a good run for their money.[7]

Arthur Carman provided a succinct assessment of White's career, when he said, 'A great forward, a fine fellow, and a clean player is 'Son' White.' Enough said.

Note: With thanks to Owen Eastwood for the research associated with White's war service.

[1] NZ Truth, quoted by Arthur Carman, NZ Sportsman, 21 May 1927

[2] Carman ibid

[3] Andrew 'Son' White, letter, 25 October, 1924, published in The Southland Times, 13 December 1924

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

[6] Andrew 'Son' White, interview, The Southland Times, 21 March 1925

[7] ibid