How fitting that the 1924 All Blacks Test against Ireland should be recalled 100 years later as the two countries line out to play each other again at the weekend in Dublin.

Much has happened in rugby in both countries since then, but Ireland has gone into the 2024 Test as the No1 team in the world. But things were different back in the day.

That Ireland was unprepared to play a Test match in 1924 would be an understatement. November was regarded as too early to be playing Test matches.

Compared to more recent times when squads practice almost all the year round, the Ireland side got together, the selection having been made on the previous season's form, and 1905-06 Original E.E. Booth, who was touring as a journalist, said the Ireland captain G.V. Stephenson was attempting to arrange 11th-hour preparations on the Friday night before the Test.

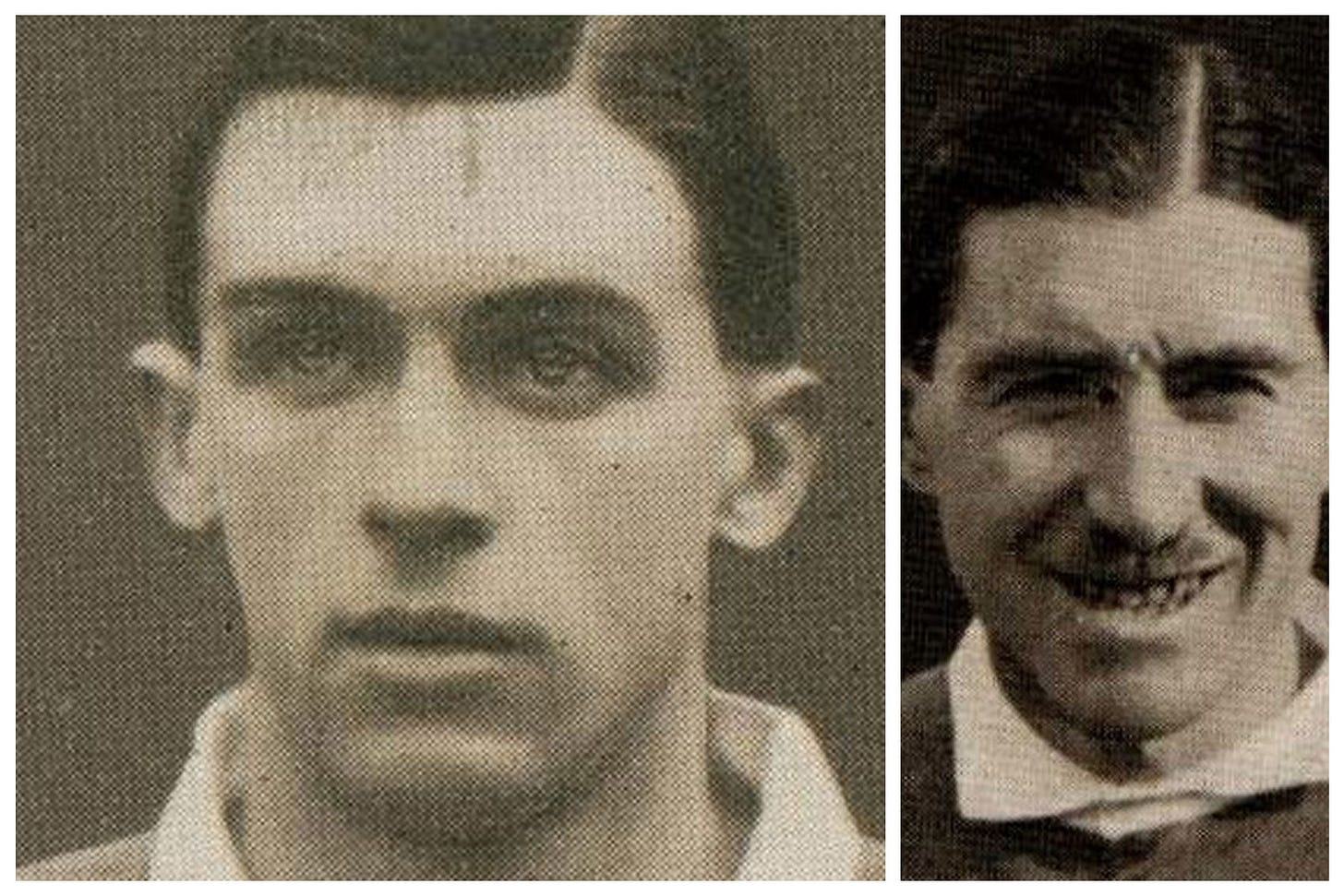

Ireland captain G.V. Stephenson (left) and fullback Ernie Crawford

Now that the Test matches had arrived, one unnamed New Zealand writer, most likely R.A. Barr, who, among the touring media, had been the most critical of scrums, wrote in The Guardian that New Zealand was practising a new scrum system ahead of the Test matches aimed at achieving the loosehead advantage.

It would not be polite to state what the new system is; sufficient to say that it should prove effectual against any three-two-three pack of scrummagers, however clever they may be in hooking the ball. The system is being practised by the New Zealanders, and will be adopted and revealed when occasion arises, and not before. Maybe it will be the 'surprise' at Twickenham in the great and final Test match, All Blacks against England on January 3.[1]

The writer took exception to the law that the halfback put the ball fairly into the scrum, and that it pass the first player on each side before the scrum operation could start.

This tendency is spoiling Rugby football in England, occasioning endless scrumming, breaking up, re-forming, and packing with the fight for the 'loose head' position. Three in the front row must always cut out two, and, whilst the 'loose head' is not of any special advantage to a side, the All Blacks are realising that they are at a disadvantage and are considering a new method and system in formation.[2]

However, the English sides, especially, had problems with how they attacked. They were adhering to the old style and system of short-line kicking, which was defensive, ineffectual, and futile in any attempt to beat the All Blacks. English sides needed to develop their attack if they hoped to defeat the New Zealanders.[3]

After their injury concerns the All Blacks looked strong for the first of their Test matches. Maurice Brownlie and Jock Richardson were consistently playing well, and Ron Stewart had improved, always seeming to be on the ball. With his speed, he was often on hand, supporting the backs to open up the game. Hopes that he would play in the Ireland Test were dimmed when he was taken to hospital suffering pleurisy, resulting in a nine-day stay in care.

Bert Cooke was the best back in the side and had scored four tries in the two games preceding the Test, while his running game made some great openings for Gus Hart to score four tries against Cumberland.

Arriving in Dublin, the Test squad left those not involved in the Test at the Royal Hibernian Hotel. The team headed for Salthill, Monkstown, to prepare. Porter's knee injury prevented his inclusion in the Test team, while Les Cupples took Stewart's place in the pack. Bill Dalley said Salthill 'was a nice, quiet spot on the seaside. It was lovely to get a sea breeze for a week.'[4]

'Ginger' Nicholls observed that when the team returned to Dublin on the morning of the Test, 'they were jumping out of their skins and never had they spent a better week in their lives.'[5]

For George Nepia, there was a clash against a great opponent in Ireland's fullback, Ernie Crawford. Wounded in the arm while serving with the 6th Royal Inniskillin Dragoons (Ulster Division), he was invalided home. Returning to accountancy after the war, Crawford had to wait until 1920, when he was 28, to make his Test debut for Ireland. He would win 30 caps, 15 of them as captain, until he retired in 1927. Something of a character, he is credited with inventing the word 'alickadoo', a title that refers to non-playing rugby aficionados.

When the tour was over, and we were homeward bound, we fell to picking out a No.1 of opponents. We were unanimous that Crawford was the best of the lot. Had it not been for the fullback, Ireland must surely have been beaten more heavily than by six points to nil. His field and kicking, too, were out of the copybook, so to speak, and I learned much from him. To me, the amazing thing about Crawford was that there seemed to be so little of him.[6]

Which of Nepia or Crawford had the best game depended on which country you came from. But both mastered the difficult conditions in which the game was played.

A three-hour rainstorm only eased in the hour before kick-off. New Zealand's cause was made more complicated after having to play into the wind in the first half and then seeing the wind turn at halftime to continue to favour the Irish. Ireland played a bustling game, no surprises there, and pressured the All Blacks' backs. When Ireland managed to secure the ball, they put their boots to it to put New Zealand on the back foot. But the All Blacks were confident enough to continue running the ball for as long as possible. Rain resumed 20 minutes into the game. It was so bad, the teams agreed to cut the halftime break to only two minutes. Twice, Hart was denied tries, once dropping the ball short of the line and then putting his foot in touch before diving in at the corner. New Zealand touch judge L.B. Simpson was overruled by referee Freethy, who said Hart's foot had gone out. E.E. Booth disagreed with Freethy's ruling.[7]

Crawford's outstanding defensive play denied the New Zealanders at least three more tries.

Mark Nicholls said running the ball was foolish as the heavy rain set in and the All Blacks pack 'were playing a great game, winning the scrums and going on with fine dribbling rushes'.

Following a great rush by our forwards, Dalley passed to me on the blind side and I ran through, Parker linking up on the outside side. Hotly pursued, I endeavoured to get to the Irish fullback to give Parker a clear run in and had almost succeeded when I was tackled. I got the ball to Parker, whom I thought was a certainty to score, but Crawford was a wonderful fullback, for although Parker was just past him he brought off a tackle which was a thousand-to-one shot. Parker and I have often talked over this incident, and Jim always says: 'I never gave him a possible chance.' Soon afterwards, Dalley and I were associated in carrying on a dribbling rush, and when Dalley had beaten Crawford, I was left in charge of the ball right in front of the goal. The ball bounced up slightly, so I gathered it in and dived over. Unfortunately, I knocked it on about three and a-half inches and was recalled. When the referee [A.E. Freethy] blew his whistle I caught his eye and said: 'You win.' He was a wonderful referee and never seemed to miss the vital incidents of a game.[8]

It was interesting that E.E. Booth commented of Freethy, given matters later in the tour.

I was not so much impressed with the referee as on former occasions. He seemed to be too full of restraining power, and the use of what is called 'advantage' and 'spirit' rulings were not a distinguishing feature. The merest failure to take a ball immaculately was christened a knock-on and whistled back.[9]

After halftime, the All Blacks scored quickly when Ireland's Harry Stephenson gathered a kick in Ireland's 25 and tried to beat Jim Parker before kicking to touch. However, Parker completed the tackle. As the ball rolled free, Parker gathered it and, on one knee, threw it to Nicholls.

With only the fullback to beat and Morry Brownlie on my right and Svenson outside of him a try was a certainty. The fullback was within two yards of the goal line, and when I passed to Morry, I thought he would score himself, but he was grasped round the wrist and fairly held, however, he got the ball to Svenson, who scored.

The Irish players in the immediate vicinity protested, declaring Brownlie's pass forward, and I think they were correct. But Freethy, the referee, was in a perfect position and he gave the try.[10]

Nicholls added a penalty goal from in front of the posts to make it 6-0 as the rain poured.

Crawford, the Irish fullback, played a masterly game. He was one fullback that Nepia did not outshine. He extricated his side from all manner of dangerous positions. His fielding and kicking was wonderful considering the state of the ball and ground. He went down fearlessly and tackled like a demon. On the day he was slightly superior to Nepia.[11]

A Wellington identity, E.H. Garbut, who had trialled for Ulster, said,

Ernie Crawford, the Irish fullback, played outstanding rugby, but Nepia was superhuman. He did things that day to the Irish forwards that had not happened before. He halted their foot rushes, and Irish attacks with the ball being tapped from player to player who were considered almost impossible to stop. But Nepia not only stopped them; he turned them to his advantage. He did not attempt to defend in the accepted way. He ignored the oncoming forwards, saw only the ball, and advanced to meet it. He made no effort to go down on it. Instead, he whipped the ball off their feet, how I don't know, broke through, spread-eagled his opponents, and invariably found touch with 30 and 40-yard kicks.[12]

Nicholls said his opposite F.S. Hewitt played well and was a demon on defence until injured.

He was, I thought, the best stand-off half we had so far met on the tour. The play of our pack was the best they had so far produced. [Son] White took charge of the pack soon after the commencement of the game and proved himself an inspiring leader. At his direction they screwed the scrum and gave the Irish side a sample of real New Zealand footwork.[13]

While it was 'a broth of a game', according to Leonard R. Tosswill, he was not convinced the All Blacks had the beating of England later in the tour. The New Zealanders could have been more clever in the dribbling rushes, the most challenging manoeuvre in rugby on wet grounds. The England team of earlier in the year was skilful in that area, and he believed by 3 January 1925, the All Blacks would be feeling the strain of touring and would be vulnerable.[14]

It wasn't a 'scientific exposition' Booth said, and that was partly due to the strong tackling of both sides, a dominant feature of the game.[15] Read Masters answered the concerns about New Zealand's scrum and felt, in contrast to Tosswill, that the dribbling rushes and forward play generally were the All Blacks best of the tour.

We collected the ball in quite four-fifths of the scrums, at times pushing Ireland over the top of it after they had secured possession.[16]

Perhaps The Daily Telegraph summed the game up best.

The match will not be remembered for its finesse. The Irishmen attempted none; the New Zealanders deferred their effort to use wile and guile till the conditions of play should be propitious, and, as I have said, they never were propitious.[17]

F.S. Sellicks said Ireland was handicapped by having to include two substitute forwards 'who had no real claim to take part in a match of this class' yet they tested the All Blacks.

The All Blacks were by no means convincing, and were obviously affected by the conditions, but they never looked like losing the match.[18]

Scorers: Ireland 0 New Zealand 6 (K.S. Svenson try; M Nicholls penalty goal). HT: 0-0. Referee, A.E. Freethy, NZ touch judge L. Simpson

NEXT ISSUE: Cliff Porter's trials

[1] NZ reporter, Manchester Guardian, 21 October 1924

[2] ibid

[3] ibid

[4] Bill Dalley, diary, 28 October 1924

[5] H.E. 'Ginger' Nicholls, NZ Free Lance, 24 September 1924

[6] George Nepia, NZ Truth, 28 October 1936

[7] Booth, NZ Truth, 27 December 1924

[8] Mark Nicholls, Weekly News, December 4, 1935

[9] Booth, ibid

[10] ibid

[11] ibid

[12] Lieut. E.H. Marfurt, Evening Post, June 1948

[13] Nicholls, ibid

[14] Leonard R. Tosswill, Country Life, 8 November 1924

[15] Booth, ibid

[16] R.R. Masters, With the All Blacks in Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia 1924-25

[17] Col. Philip Trevor, Daily Telegraph, 3 November 1924

[18] F.S. Sellicks, The Cricketer, January 1925