As the All Blacks were Britain-bound, many of Britain and Ireland's best players were touring South Africa with the British & Irish Lions.

It wasn't the most successful of visits. In their 21-game programme, including four Tests, they won nine, lost nine and drew three. They failed to win a Test and were saved from a whitewash by their 3-3 draw in the third Test.

Playing below full strength, the British & Irish Lions faced a heavy injury list. They played several games with players appearing out of their usual positions, a clear indication of the challenges they had to overcome. The absence of key players like England lock Wavell Wakefield, and two critical Scottish backs, G.P.S. 'Phil' McPherson and A.L. Gracie, was a significant blow to the team.

The team captain, England lock Dr. Ronald Cove-Smith, said,

Considerable difficulty had been experienced in collecting a representative side, but of the twenty-nine players selected, the forwards formed a formidable array.[1]

Injuries proved so severe on tour that it might have stopped at one point. With the regular and outstanding Scottish fullback, Dan Drysdale becoming so stale with the number of games he had to play without a break, two forwards and two wings each played a game out of position to help him recover.

...but outside the scrum and particularly in the centre [we] had no one capable of coping with the wily [centre Pierre] Albertyn. In fact, owing to the weakness here, both in attack and defence, we were forced to sacrifice weight in the scrum and play a couple of winging forwards, in the hope they would be speedy enough to get across and cover up the deficiencies. At first this policy paid, but before long it was spotted and effectively countered. The inherent weaknesses of the team could not, however, be covered up for long, and manfully though the fellows tried they were no real match for South Africa in the Test games, where superior speed and experience outside the scrum eventually took its toll.[2]

Several of the tourists figured prominently in games against the All Blacks. Cove-Smith played for England, while other players who would appear against New Zealand were loose forward Tom Voyce, Freddie Blakiston, Newport inside backs Harold Davies and Vince Griffiths, and Swansea and Wales three-quarter Rowe Harding. But if the organisers expected benefits to be used against the All Blacks they didn’t materialise.

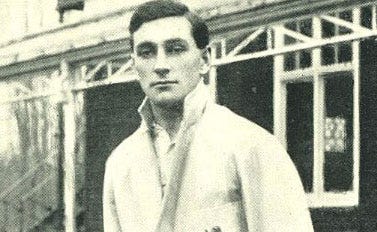

England and British and Irish Lions wing Rowe Harding (pic from his biography, Rugby Reminiscences and Opinions, The Pilot Press, Strand, London, 1929)

To get an idea of what the All Blacks might expect from some of Britain's best players, A.H. 'Arthur' Carman, who decided to follow the tour as a journalist, made his way via South Africa, dropping in on the Lions tour.

That also allowed him to write for South African and New Zealand newspapers to help pay his way. However, because of the shipping of mail, his reports landed in Wellington around six weeks after the All Blacks tour had started in England.

Watching the fourth Test in Cape Town on September 13, he felt New Zealand was a more attacking side.

New Zealand inside backs beat the opposition far more than is the case here, and display generally more initiative in cutting-in and side-stepping. Of course, these positions are usually filled by small, light, nippy players, who are able to dodge round more easily.

One especially good feature of yesterday's play was the fine tackling of both sides, and it is in this phase of the game that the 'All Blacks' will have to improve greatly. The large scores piled up in New Zealand are almost solely the result of poor defence, and when players are willing to go down to it and tackle as well as was the case yesterday there is not much cause for worry.[3]

After watching the Test, Carman wrote in the Johannesburg Star that with the Lions playing better than South Africa, he could not say who would win the Test at Twickenham on January 3 between England and New Zealand. He felt the All Blacks would be slightly favoured because they were playing only England and not the Lions side.

Among the Lions players, Ian Smith impressed, and if paired with Wallace and Harding for England, they would cause problems for New Zealand.

How we shall long for the Jack Steel the Springboks of 1921 knew. The whole British back division is fast and very few players in this country can equal them in speed. The men are also outclassed by the brainier Britons, and until South Africa can breed backs of the same class she cannot expect to gain a superiority through her backs. The British players are more of the same standard as this year's All Blacks, and it will be interesting to follow the play of these men when they met the wearers of the 'Silver Fernleaf' on their return to England."[4]

Carman said both South Africa and the British team were defensively superior to New Zealand.

We in New Zealand seem to regard tackling as useless, and the result is high scores both sides. Unless this is improved before our team reaches England, they will not be able to show a record at the finish of 32 matches. I have seen no players here with the quickness and knack of breaking through as well as does Albert Cooke, the young Auckland five-eighths. He is a real find, and as slippery as an eel. He played a wonderful game in the final trial game at Wellington, North versus South Islands, and broke through with remarkable speed; it was almost solely through openings made by him that the North won by 30 points to 5 [sic]. He should finish up the tour hailed as another Jimmy Hunter.[5]

Carman pointed to another prospective area of concern, scrummaging. He said the repetitive scrummaging that marked the South African Test was wearying. He said players of international ability should be able to play without continually infringing.

With all the talk about the New Zealand wing-forward, he does not cause the whistle to blow as frequently as it did on Saturday.[6]

He made the point that a Sydney newspaper reported Cliff Porter was only penalised once against Australia earlier in the year, and that was down to a referees' error. New Zealand's use of the 2-3-2 scrum provided fast ball and allowed the scrum to break up immediately; there was no prolonged pushing. It suited New Zealand's game as they liked to give the ball as much air as possible.

The main duty of the forwards is, therefore, to let the rearguard have the ball on every possible occasion; to join in a passing rush themselves whenever they can. So far in this country, I have not seen the forwards come round and take their part in a bout of passing.[7]

Another view of what the All Blacks could expect was provided by R.H.W. Lowry, a brother of future New Zealand cricket captain T.C. 'Tom' Lowry. He was returning from study at Cambridge University. R.H.W. Lowry, Tom Lowry, and another brother, J.U. Lowry, were all Cambridge 'blues' (R.H.W. at rugby, T.C. at cricket and J.U. at tennis). R.H.W. said the All Blacks would find England a different proposition to the side of 1905. He had an ominous warning regarding the 2-3-2 scrum the All Blacks used.

New Zealand will not be able to play the two-three-two formation in the scrum in England. The English Rugby Union [sic] have ruled that the forward nearest the side from which the ball is put into the scrum must not hook the ball. This means that if they All Blacks have two men in the front row only one of them will be allowed to hook. They will thus have only one man hooking against two. It has puzzled me not a little as to how New Zealand is to get over this ruling.[8]

However, Lowry felt Wales was unlikely to be a problem. Changing the selection method to a nomination system caused clubs to swamp the selectors with players without satisfying the side's performance.

Given the nature of their rivalry, only three years old, South Africans were keen to see how the All Blacks did after the British tour to South Africa. They were concerned that many believed the 1924 All Blacks were better than Dave Gallaher's side of 1905-06. South Africans knew that at that time, they could not field a side to match the South African sides who toured Britain in 1906-07 or 1912-13.

And when we last sent a team to New Zealand we thought our stock was so low that we were in for a big hiding, but we did not find the New Zealanders such formidable fellows as we had thought. We did well, not because we were a great combination, but because New Zealand was not as good as she had claimed. If, on the other hand, there is every reason to believe that the All Blacks have today the greatest Rugby combination in the history of the country, there is little doubt that they could whip the world – certainly as far as South Africa is concerned. While our Rugby has always stood the test against that of other countries, we hold no claim to being able to produce a fifteen such as Gallaher skippered. We still think we have the men to master both Britain and New Zealand. The latter, in 1921, were said to possess a wonderful combination, and we knew we did not, yet we lost only two matches in 24, which goes to show that we were either underrating our own virtues or that New Zealand were overrating theirs.[9]

Yet, they believed New Zealand must have found a way to improve rapidly because if they could turn out a team equal to, or better than, Gallaher's side, there was no evidence of it during their 1921 tour. They would follow the tour with interest because they doubted New Zealand was as good as they believed. They couldn't get the better of a South African side in 1921 that was not rich in talent.

Another view was provided by peripatetic correspondent E.E. 'General' Booth, a member of the 1905-06 side who had turned to journalism after the tour and covered rugby in Australia, England, and South Africa.

He informed readers of the Johannesburg Star that the only member of the side who toured South Africa in the N.Z. Army team in 1919 was Alf West. Booth said the tour of Australia was a godsend for the team as it allowed them to work off condition and develop cohesion and confidence. The forwards were most proficient in lineouts, but their forte was in hand-to-hand passing, with several forwards fast enough to qualify as backs.[10]

Next issue: What should the All Blacks expect?

[1] Dr Ronald Cove-Smith, British Team in South Africa, 1924, in History of South African Rugby Football, Ivor Difford, The Speciality Press, Wynberg, Cape, 1933

[2] ibid

[3] A.H. Carman, The Dominion, undated

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

[6] Carman ibid

[7] ibid

[8] R.H.W. Lowry, The Dominion, 26 June 1924

[9] 'Springbok', Sporting Chronicle, Manchester, undated

[10] E.E. Booth, Johannesburg Star, 23 August 1924